The Good-Doers

Cover Story: Little Richard Lifts Us Up

By Traci Burns

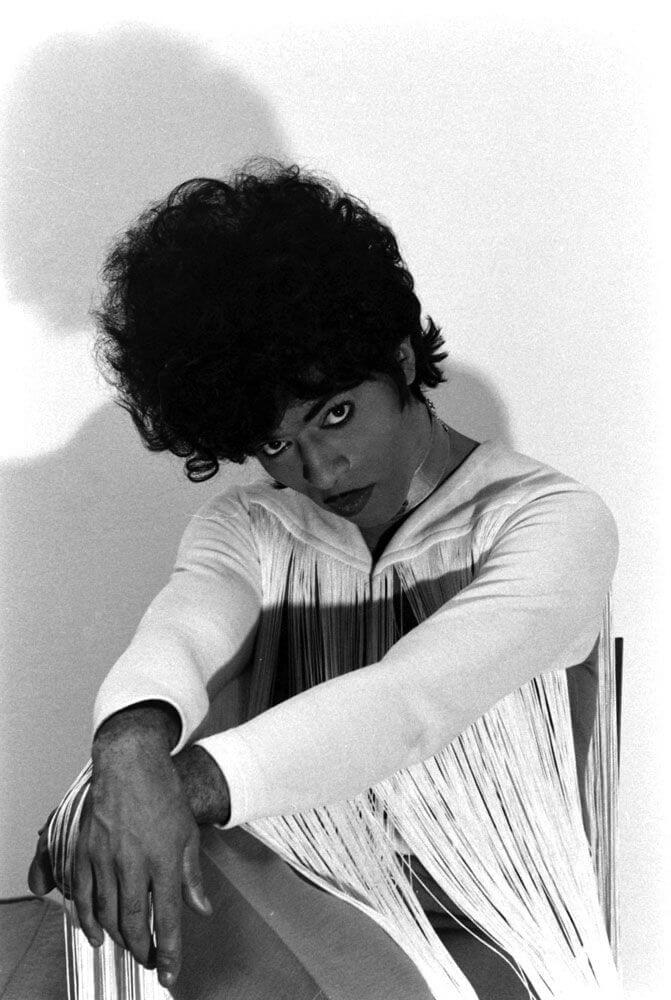

Photo by Maryann Bates

Rest in peace and power, Little Richard. The Originator. The Architect of Rock ‘n’ Roll. An original Good-Doer.

As news of Little Richard’s death began to circulate on the morning of May 9, it was hard not to feel devastated, especially for those of us living in Macon, Richard’s oft-shouted-out hometown. We don’t always get everything right here, but we’ve proved that we’re fertile soil where musical revolutionaries blossom and flourish, and you don’t get much more revolutionary than the self-proclaimed King and Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll. Little Richard makes us proud to say where we’re from.

2020 isn’t playing fair. First, a global pandemic wreaks havoc on our lives, and now you’re telling me that the originator, the innovator, the emancipator, the “Architect of Rock ‘n’ Roll” is gone? We have to live without that vital, vivacious man, that catharsis-made-flesh, that beautiful, brave, boundary-annihilating genius? As Little Richard himself would say: Shut up!

Many of us, searching for a way to mourn, turned to his music, cranking up groundbreaking, iconic tunes like “Tutti Frutti,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Lucille” as we absorbed the grim reality of a Little Richardless existence. But the best musicians live forever through their art, and anyway, who could mourn for long with that frenzied piano banging out the holiest unholy rhythm, with those unhinged screams promising joy and liberation?

“The energy in his music is so profound,” said Mercer University art professor Craig Coleman. “When you listen to it, you really can hear the whole history of rock ‘n’ roll.”

After all, Little Richard was rock’s architect – just watch any interview with him, he’ll tell you. He teased his hair, lined his pretty eyes, hiked his foot up on that piano and went wild, setting the stage for the paradigm-shifting, provocative culture of the 1960s and transforming into an icon for outsiders and rebels everywhere.

The words “icon” and “rebel” have wildly diverging connotations, depending on the audience. In downtown Macon, a Confederate memorial statue stands at the corner of Cotton Avenue and Second Street in the same spot where 19th century slave auctions took place. Its presence is divisive – some want the oppressive symbol demolished or moved elsewhere; some say we should leave history be. Maconite Maggie Gonzalez captured the zeitgeist and made the news by creating a Facebook group whose name – “Tear Down Crusty Confederate Dude; Erect Fabulous Little Richard Statue” – is also its goal.

“I’d love to see us greet the people who come to Macon with something really positive about our past,” Gonzalez said.

Coleman happened to see that group posted on Facebook on the Saturday that Little Richard died. He’d been listening to Little Richard’s music all day and considered how accessible that Confederate statue was from the big front window of Mercer’s McEachern Arts Center on Second Street. As an artist who works in mixed media and digital imaging, Coleman had projection equipment readily available, and he was flush with ideas from a symposium on activist art he’d recently taught.

On the evening of May 9, with the streets downtown mostly empty, Little Richard showed up and showed out, as he always did. Coleman projected black and white images of our beloved beauty-on-duty onto that tall, pale statue and before long, photos of the one-off art installation were making the social media rounds, garnering praise for the fitting tribute and the cheeky yet substantial message conveyed.

“I felt that the symbolism of this, his image on that statue – that was important,” said Coleman.

‘Comin’ out of Macon, Georgia’

Just by being his authentic and undiluted self, Little Richard changed the world, and he never let the world forget that it all started in Macon. Countless artists and musicians were inspired by his larger-than-life presence. The mixed-race audiences who congregated at his early shows to swoon, sweat and dance made segregation look as ridiculous and outmoded as it was.

Audiences ate him up, always, no matter what he was doing or how long he’d been out of the spotlight. Musical talent isn’t enough – you’ve got to have that thing, Little Richard once explained.

“I always did have that thing, but I didn’t know what to do with the thing I had,” he said. “I always had my little thing I wanted to let the world hear.”

We heard you, loud and clear, Little Richard, and we miss your voice already.

“I look back on my life, comin’ out of Macon, Georgia – I never thought I’d be a superstar, a living legend. I never heard of no rock and roll in my life. Black people lived right by the railroad tracks, and the train would shake their houses at night. I would hear it as a boy and I thought: I’m gonna make a song that sounds like that.”

Richard Wayne Penniman grew up in a shotgun house in Pleasant Hill, clamoring for attention alongside 11 siblings. Religion was an integral part of his young life. His grandfather and uncle were preachers, and his mother, Leva Mae, met Bud, his father, at a church revival. Bud Penniman was a deacon, but he also ran a juke joint and sold moonshine on the side. Richard was born into that dissonance, and would spend his life pinballing between the sacred and the profane.

Singing was omnipresent during Richard’s childhood. He sang in church with gospel groups, but music also swelled from the front porches and backyards of neighborhood homes, from living rooms full of sweet grandmas and aunties during Wednesday evening prayer meetings.

“There was so much poverty, so much prejudice in those days,” Richard once said. “I imagine people had to sing to feel their connection with God.”

There was prejudice, too, against boys like Richard, boys who idolized their mother and imitated the way she talked, who would sneak into her bedroom sometimes to use her perfume and makeup, who always wanted to be the mama when playing house with his cousins.

“I felt like a girl,” Richard said, “so the boys wouldn’t play with me ‘cos I’d been saying stuff like that.”

Richard was born with one leg shorter than the other, and kids made fun of the effeminate way he walked to compensate, calling him “faggot, sissy, freak, punk,” he said. “They would call me anything.”

As he grew older, name-calling turned to physical violence. He was scared to walk the neighborhood solo or hang out with any of the unpredictably brutal boys, but he couldn’t shrink himself to be safe, either. He had a need to be seen for who he was.

The truth behind ‘Tutti Frutti’

As a teenager, Richard sold refreshments at the City Auditorium, where Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the pioneering guitar player, gospel singer and rock ‘n’ roll foremother overheard him singing her songs before the show. Impressed and sensing a kindred spirit, she invited him to open the show for her that night, and made sure to pay him well.

From that moment, performing became Richard’s singular pursuit; his fascinating array of formative experiences molded him into a dynamic artist. Kicked out of his house at 14 by a homophobic father who bitterly rebuked him as “half a son,” Richard crashed at the home of Ann’s Tic Toc owner Ann Howard (who he considered a second mother) and sang backup with bands that played there, toured the Chitlin’ Circuit, went on the road with black vaudeville shows and snake oil salesmen, and performed as his drag alter-ego Princess Lavonne.

His nonstop energy landed him a record deal with RCA, and by age 18, he’d had his first recording session. His early music is good, but missing the unhinged chaos that’s an earmark of his sound. When his father was murdered by a patron of his own bar, Richard moved back home to help provide.

Around that time, he met Esquerita (born S.Q. Reeder Jr.), a South Carolina native and fellow performer. Richard was fascinated with Esquerita’s large hands, and with the noises he could coax from a piano with them. Esquerita also wore pancake makeup, eyeliner and a cartoonishly large pompadour. Richard took notes.

In September 1955, Richard traveled to New Orleans to record for Specialty Records. He’d spent the previous year hounding label owner Art Rupe for the opportunity, but his studio performances lacked the fire of his live show. Producer Robert “Bumps” Blackwell called for a break and took the singer to a nearby bar, where Richard beelined for the piano and pounded out something he’d written – a wild, nasty song that always electrified a crowd, a song whose now-iconic nonsense refrain “Awop-Bop-a-Loo-Bop Alop-Bam-Boom” began as a sassy euphemism Richard would holler at work in lieu of the swear words he wished he could unload on his manager at the Macon Greyhound station where he washed dishes.

Blackwell’s jaw hit the floor. The lyrics to “Tutti Frutti” were wildly risqué for the time – “aw rooty” was originally “good booty,” for starters – but the producer knew a hit when he heard one. A songwriter who’d been hanging around the studio helped with a sanitized re-write, and, at the very end of their allotted time, pushing through hoarseness and exhaustion, Little Richard banged and clamored and “Woo!”-ed his way through an exuberant recorded version of the song that would make history and etch itself into our collective cultural consciousness.

Undeniable influencer

In Georgia Public Broadcasting’s 2018 documentary “The Macon Sound,” the late Capricorn Records impresario Phil Walden said, “When I first heard Little Richard say ‘Awop-Bop-a-Loo-Bop Alop-Bam-Boom,’ I knew I didn’t want to sell insurance. I didn’t want to be a doctor, lawyer or an Indian chief. I wanted to be in rock ‘n’ roll.”

We know that story well – Walden and his brother Alan went on to help launch many iconic music careers, among them Otis Redding’s. Otis grew up idolizing Richard, as did James Brown, but when the sonic bomb of Little Richard detonated, the hometown folks weren’t the only ones left shaken.

Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr and Keith Richards all adored Little Richard. He was Elton John’s biggest influence. Waylon Jennings, a fan since the beginning, got fired from his first job as a DJ for playing two Little Richard records in a row. Filmmaker John Waters styled his iconic pencil-thin mustache after the one Little Richard wore. Little Richard taught Mick Jagger how to strut his stuff onstage and Paul McCartney how to woooo! He taught whole generations of gender-fluid, nonconforming misfits how to weaponize their differences in the name of art – think of David Bowie, Prince, Lady Gaga and Janelle Monae.

Lou Reed, whose work with the Velvet Underground influenced countless avant-garde musicians, said this about hearing Little Richard for the first time: “I wanted to go to wherever that sound was and make a life.” And punk icon Patti Smith said that hearing “Tutti Frutti” “awakened a positive anarchy in a little girl’s heart. Nothing was the same after hearing his exciting and excitable voice.”

In those years – in any years, really – nobody had ever seen anyone who looked like Little Richard. With his big hair, flashy clothes, penchant for pancake makeup and eyeliner, and that Cheshire-cat grin on his face, he was captivating – and he knew it.

“They don’t like to dress like I do – I like to put it on,” Richard, clad in a pink fringed blouse and sparkling headband, said smugly in a 1972 interview. “When I walked in the airport in London today a man dropped his cup of coffee.”

Alan Walden recalls being a teenager in Macon, sneaking out to check out the music scene downtown, then bam! There was Little Richard, in the flesh.

“Richard stepped out of a cab in a flaming red suit – I mean blood red, bright as could be,” Walden said. “He had this parasol, which was red as well.”

Walden was stunned into shy silence, but his braver friend shouted out, “Tutti Frutti!”

“And Richard turned around and shook his behind and struck a pose and said, ‘Good booty!’” Walden laughed. “That’s etched in my mind for life.”

Bisexual, omnisexual and gay

Little Richard’s sexuality is something he grappled with in a public, vulnerable way throughout his career. Though he often presented as thrillingly confident in his queerness, he doesn’t seem to have been granted much internal peace on the topic. But the fact that he talked openly about his preferences at times when other public figures wouldn’t dare was revolutionary. He would often switch up the label he gave himself – bisexual, omnisexual, gay, ex-gay, even once during an interview with Joan Rivers cracking himself up by saying, “I am gay, yes – I’m the originator! I think I was the first one of them, too!”

Onstage, Little Richard was a juggernaut. He harnessed every bit of his power and worked the crowd with a combination of Sunday-service intensity and pure sensual allure, singing and playing with otherworldly fervor, baptized in his own sweat. A true theatrical showman, he refused to be upstaged, and gave everything he had to his audiences, including his clothes. He was known to climb on top of his piano and toss his sweat-soaked garments out into the frenzied crowd, a holy communion of sorts.

In the Jim Crow 1950s, black and white audiences were assigned separate seating areas in venues, but nobody went to a rock ‘n’ roll show to follow the rules. Little Richard’s early concerts were liberating and liberated. It’s been said that the very first panties ever to be thrown onstage were tossed at one of his shows in 1956 – and everyone wound up commingled and sweaty on the dance floor.

This was the best of human nature, this organic desegregation, and it terrified the establishment, who looked for any way to undermine Little Richard’s popularity. Milquetoast Pat Boone recorded a bland cover of “Tutti Frutti” that somehow out-charted Little Richard’s version. Not to be outdone, Richard wrote his next hit, “Long Tall Sally,” faster and wilder, so squares like Boone couldn’t keep up. Boone still recorded a cover, but this time Little Richard trounced him on the charts.

In a 1990 Rolling Stone interview, Richard graciously referred to Boone’s covers of his songs as a “blessing.” They were played on white radio stations, and helped more white audiences learn who Richard was and what he was doing.

“I believe (Boone) opened the highway that would’ve taken a little longer for acceptance, so I love Pat for that,” Richard said.

Jamie Weatherford, who co-owns Macon’s Rock Candy Tours along with his wife, Jessica Walden, tells another story of Richard’s generosity and influence: During a Little Richard performance in Toccoa, Georgia, in 1955, a young gospel band hopped onstage during intermission and began to play. Most artists would be infuriated at the attempt to steal the show, but not Richard. Instead, he told the bandmates about his manager in Macon, Mr. Clinton Brantley, a music promoter who also owned the Two Spot at the corner of Fifth and Walnut streets. That next week, the Gospel Starlighters showed up (unannounced, yet again) to perform for Mr. Brantley, who liked them so much – especially their energetic lead singer, a young man named James Brown – that he signed them on the spot.

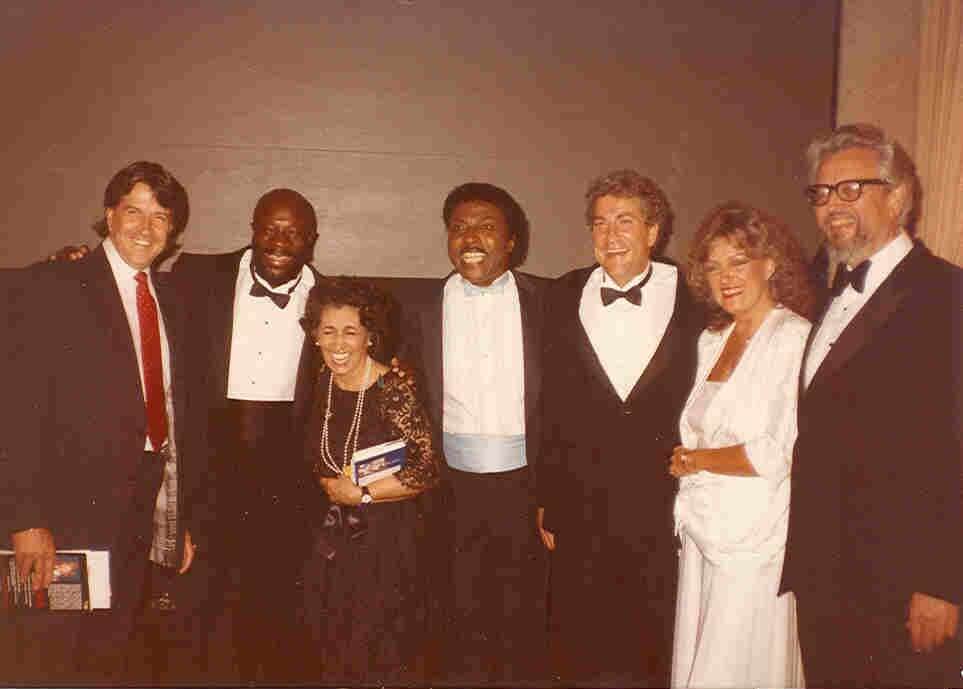

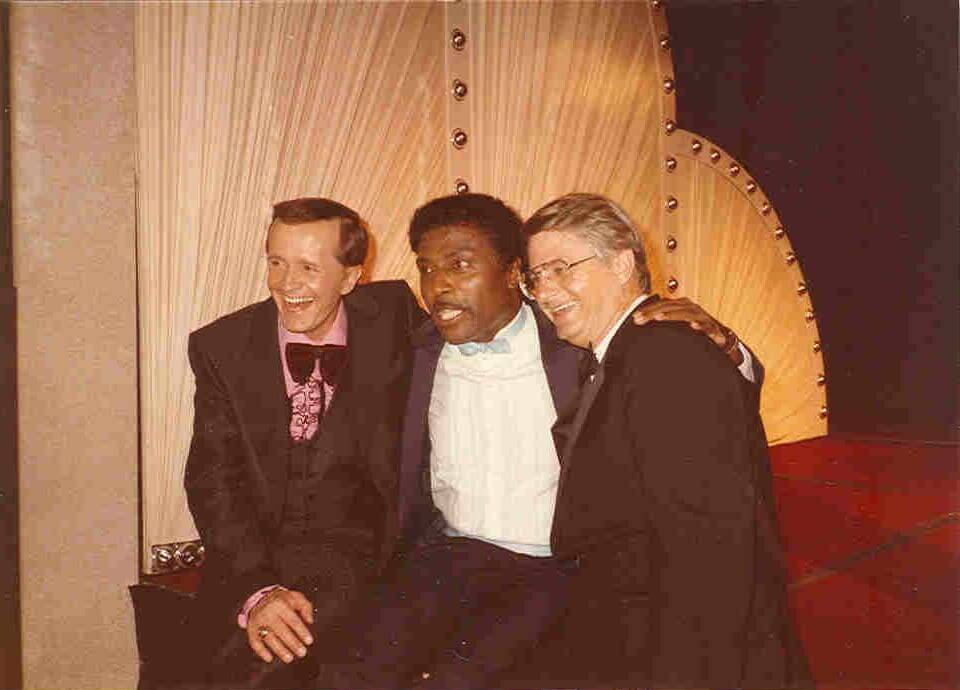

Photo courtesy of Lowery Music Group Archives

‘And the winner is … me!’

After casually annihilating the dominant paradigm of the day, inspiring the most exceptional entertainers of our time and creating the template for rock ‘n’ roll in the process, Little Richard, gripped by religious guilt, retired at the height of his fame in 1957. He earned a degree in theology, was ordained a minister in the Seventh Day Adventist Church, got married, adopted a son and started recording gospel music.

Neither his renunciation nor his marriage lasted too long, and in the early 1960s he was on the road again, backed by a band that included Jimi Hendrix on guitar, and supported by the then-unknown Beatles, who adored and absorbed Richard’s every move.

Little Richard was never able to recapture the frenzy of his earliest days on the music scene, but he didn’t need to. He sold more than 30 million records worldwide. The imprint had been made, the influence was – and is – apparent.

As all superstars do, Little Richard stayed in the spotlight for decades, charming hosts and audiences alike on late-night talk shows, singing the theme song for “The Magic School Bus,” taking a critically acclaimed turn onscreen in 1986’s “Down and Out in Beverly Hills,” popping up as a guest star on “Full House” or “The Simpsons” and hamming it up in commercials for Geico or Taco Bell. Little Richard always stole the show, whatever the show happened to be.

In 1986, the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame chose Little Richard to be one of its inaugural inductees; at that time, he’d never won a Grammy. Two years later, while onstage to present the Best New Artist award at the 1988 Grammies, he took the opportunity to speak his mind. Teasing the envelope open, Little Richard saucily declared, “And the winner is … me! I have never received nothing!” The audience leapt to their feet, cheering and applauding, as Richard went on, “Y’all ain’t never gave me no Grammy, and I have been singing for years!”

His bemused tone had an obvious sharp edge behind it – he often felt a deep sense of injustice as a result of not getting the credit he knew he was owed.

Richard would go on to win a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1993, three years after Paul McCartney won his. Paul McCartney was on record saying that Little Richard taught him everything he knows, and sat under Richard’s tutelage practicing that signature woooo! until he got it down-pat – just listen to his cover of “Long Tall Sally,” you’ll hear it. Despite this mentorship, McCartney didn’t mention Little Richard once in his acceptance speech, and that stung.

“I just don’t understand some things sometimes,” Richard said. “I was sitting there in front of him, and he didn’t say nothing. It makes you feel like crying, you know?”

Faith, sexuality and mortality

Over the last decade, health problems slowed Little Richard down – sciatica pain, hip replacement surgery that eventually led to him needing a wheelchair full-time and a heart attack. He’d been out of the public eye for some time when, on May 9, Richard’s son Danny confirmed that Richard died of bone cancer at his home in Tennessee after several months of illness.

Brushes with mortality caused Richard to focus squarely on religion in his later years. Some of his last public appearances, on a Seventh-Day Adventist broadcasting network, find him rejecting homosexuality, urging audiences toward salvation and giving passionate testimony against worldly pursuits like rock ‘n’ roll.

When he gets going, he’s as dynamic and compelling as ever, but hearing about the evils of “unnatural affection” is a little painful coming from the man who was so visibly, thrillingly “unnatural” in his heyday that he was the most natural thing in the world. Still, it’s a small comfort to hear him say, “Regardless of whatever you are, (God) loves you.”

Little Richard struggled to balance all his most intense impulses. His sexual desires didn’t jibe well with his religious background, and being a religious rock ‘n’ roll performer felt impossibly hypocritical. He ricocheted between these identities for years, at great damage to himself.

“The tragedy of Little Richard is that he demonized his sensuality and buried his career along with it from 1957 to the mid-1960s,” said Mercer professor Andrew Silver. “For a time, he decoupled the sacred from queer sexuality, ministry from music. But when he came back, he was preaching the gospel of the fabulous … trying to invent a way to bring the divine into the world of the sensual.”

Love for Macon, Georgia

“I have taken this beauty all over the world. I have taken it to places where people didn’t even think it was beautiful. One man told me: ‘Go back to Africa where you came from!’ I said, ‘Africa? Who told you I was from Africa? I’m from Macon, Georgia. I am a peach.’”

To hear Macon tell it, we’ve been adoring supporters of Little Richard throughout his entire career, but the truth looks a bit different. Maconites who are old enough to remember when Little Richard was still a fixture around the city paint a picture of a charmer, a sharp dresser, a sweet and talented young man who was always singing and performing while working one of his many jobs. But the straitlaced, racist mid-1950s city leadership did not feel that Macon was the place for someone as outrageous as Richard, and he was often not treated well here.

“Little Richard was a fearless outsider, and so far ahead of his time that he often seemed alien,” said Jared Wright, a Macon-based archivist, curator and musician. “He was a fabulous storyteller and walking myth, yet he was humble and never failed to mention his love for Macon. That love, unfortunately, went largely unreturned during his life. Little Richard’s importance to the existence of any musical heritage in Macon cannot be understated and ought to be put on full display.”

In a late-in-life interview clip, Richard discusses getting run out of town for daring to ride in a car with a white woman. A little investigation into that incident shows that he might have been doing more than riding, but that doesn’t excuse the way he was treated, which was so harsh that he refused to return to Macon during the height of his fame.

“I didn’t go back ‘til the fame had died down,” Richard said, “and now they’re naming streets after me.”

Eventually Richard reconciled his feelings and became a great public champion of our city.

“Little Richard was generous with his love for Macon,” said Weatherford. “Despite the racism, despite being taken to the county line and being told never to return, Little Richard never missed an opportunity to talk about his love of Macon, calling it one of the ‘greatest places on this earth’ on nationally syndicated shows and beyond. No other artist in our city’s history has used their platform of fame to do more for Macon than Little Richard.”

‘Ask Little Richard’

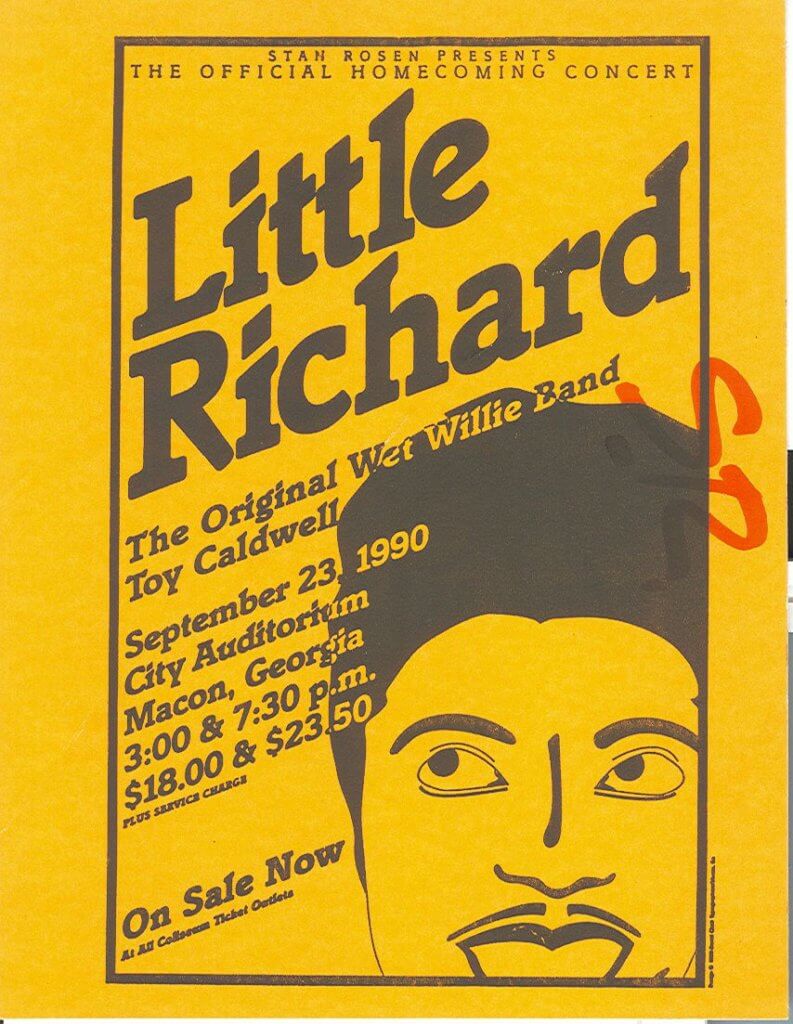

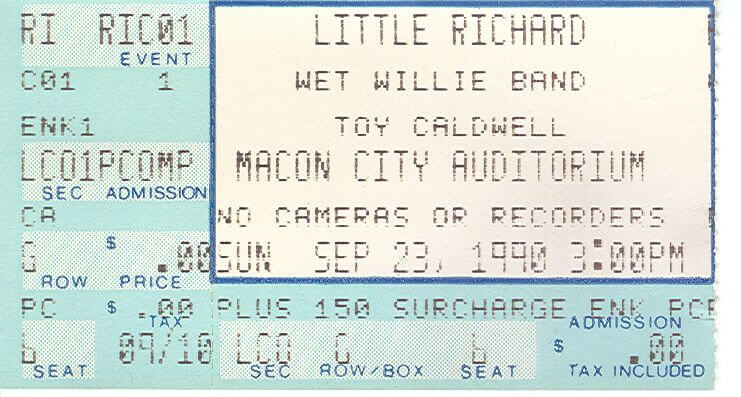

In 1996, despite the chilly rain, fans lined up behind police barricades hoping to glimpse their favorite musician heading into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame’s opening ceremony.

“There were so many stars there – B-52s, members of R.E.M., Travis Tritt, the Pips – but when Little Richard walked in with his presidential entourage, everybody’s eyes went to him – like, forget all y’all! Little Richard is HERE!” said Derrick Chatman, who worked at 97.9 WIBB from 1994 until 2002.

After the ceremony, Chatman got a little time to talk to the star and was surprised when Little Richard handed over his personal phone number.

“He wanted to talk with me about a project he thought should happen in Macon,” Chatman said.

What Little Richard wanted was an honorary doctorate from Mercer University.

“He felt let down that he’d been honored all over the world, but not in his own hometown,” Chatman said.

Eager to get Richard the recognition he deserved, Chatman wrote a few letters to higher-ups, to no avail. Seventeen years later, Little Richard got his dues, receiving his honorary degree from Mercer while decked out in a blue sparkly suit and matching cowboy boots.

“Nobody else remembered that I tried to make this happen years earlier,” said Chatman, “except for Richard. He called me, and he thanked me; he remembered.”

When you called Little Richard, Chatman said, he would disguise his voice as a way to screen his calls. He’d pretend to be someone named Pearl, or an assistant, but Chatman could always tell it was Richard.

One day, after making it through Richard’s rigorous screening process, Chatman, who had discovered that he could do a spot-on Little Richard impersonation, asked permission to do the famous voice on air.

“If you think you can do it, baby, go ‘head on and do it,” said Richard. So, for four years straight, every Wednesday on the Kevin Koolin’ Fox Morning Show, Chatman helmed a segment called “Ask Little Richard.”

“Every week I had people fooled with that show,” Chatman said. “I’d have people calling in from their job at the car wash, asking if they could wash Little Richard’s limousine.”

In 1999, Ruth Sykes asked Little Richard if he would consider being Macon’s Goodwill Ambassador for Tourism. Sykes, who spent 23 years with the Convention and Visitors Bureau (now known as Visit Macon), met Richard and his publicist a few years earlier at the Georgia Music Hall of Fame opening, and he responded to her query with an immediate yes – “and he wouldn’t take a dime,” Sykes said.

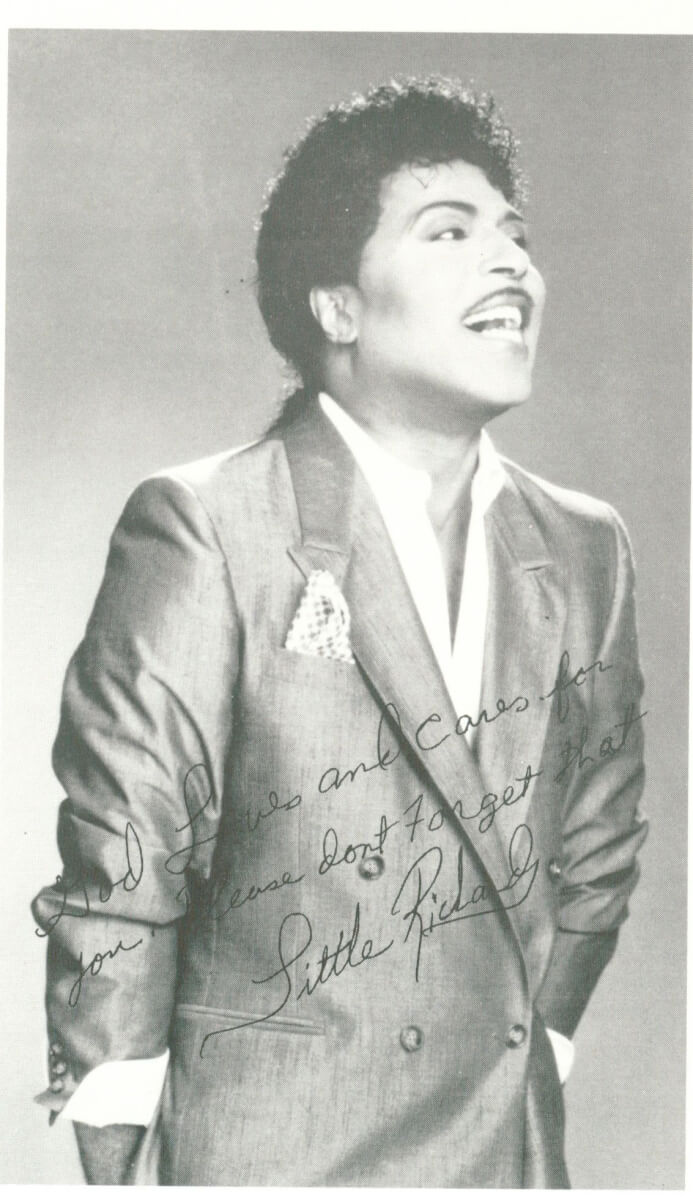

Richard made himself available in every way he could, providing a fun headshot for promo materials, allowing a video crew to film a greeting from him, even recording voicemail messages and other snippets to be intermingled with his music when callers to the CVB were placed on hold.

“It was always funny when you picked up a call and the caller said, ‘Wait! Can you put me back on hold? I was listening to that!’” said Sykes. The next year, Little Richard was the featured entertainer for the Cherry Blossom Festival. To honor him, Sykes and her team toured the city with two of Richard’s aunts, who told stories of the Macon places that had been important to him. An artist was commissioned to paint a montage of these formative spots, and the finished product was presented to him at a Douglass Theater VIP event.

“Little Richard was kind, funny, generous and so grateful to be officially part of his hometown’s marketing efforts,” said Sykes.

Photo courtesy of Lowery Music Group Archives

Honoring his humble beginnings

Ava Henderson’s family lived one street over from Little Richard in Pleasant Hill. Her great-aunt remembered Richard coming over and asking to borrow her Coty perfume and face powder. She let him, of course, and he’d leave, singing at the top of his lungs.

Years later, Richard pulled up in his limo – this was during one of the periods when he’d left rock and taken up the ministry – to pay his respects when her great-grandfather passed. The kids were spellbound, especially when Richard took the time to wave goodbye to them.

“We started screaming and waving right back,” Henderson said fondly. “We were the talk of the neighborhood for a while.”

Little Richard came from humble beginnings, and throughout his career continued to proudly exemplify the city – and the neighborhood – that shaped him. That kind of representation is invaluable; nothing can replace the inspiration and motivation that comes when a child learns about the legendary, world-renowned career of someone who looks like they look and who used to live where they live.

In 2017, Macon preserved an important part of history when we moved Little Richard’s childhood home from Fifth Avenue, where it was in danger of demolition due to interstate expansion, to its current location on Craft Street. In 2019, the renovated home opened its doors as The Little Richard House Resource Center with the goal to serve and uplift the surrounding community and keep the spirit of Little Richard flowing.

Now, thanks to Friends of the Little Richard House and the Community Foundation of Central Georgia, Richard is going to get the statue he deserves. The two organizations recently partnered to create a fund that will enable a statue of Little Richard and a replica of his Hollywood Walk of Fame star to be built outside his childhood home. The fund also will be used to support music education for low- and middle-income students throughout Macon.

Pleasant Hill is “a very warm place, a powerful place … a place of realness, a spiritual place, a black African gifted place, and that is what Little Richard represented,” said Friends of the Little Richard House board member George Muhammad. “This is the legacy that we have been given by the grace of God, and now we have a charge for the future generations.”

The goal is for the statue to be completed by Dec. 5, which would have been Little Richard’s 88th birthday.

Griffith Family Foundation Executive Director Tonja Khabir also will be partnering with the Little Richard House to offer community member-led tours of the singer’s Pleasant Hill neighborhood. Three separate tours will showcase noteworthy and influential music history, educational icons and community figures.

“The Little Richard House is such an asset to our community,” Khabir said. “It continues to tell so many stories that are relevant to us all.”

‘You can’t do without love’

We’re lucky to have even more visual representation of that great beauty in town. Last year, artist Chris Veal painted a wonderful wall-sized Little Richard on the side of Triangle Arts, an art space and event venue on Lower Elm Street.

“Little Richard seemed to have always been able to power through whatever obstacles and social norms he faced with a great deal of persistence,” said Ric Geyer, founder of Triangle Arts. “His lesson is a great lesson for all times, but maybe especially for this time.”

Triangle Arts welcomes visitors to check out the mural in person.

Brad and Meagan Evans, owners of the Society Garden, reached out to the community for fundraising help on May 12, just a few days after Little Richard’s death. Their plan: to have renowned graffiti artist JEKS memorialize Little Richard with one of his hyper-realistic outsized portraits on the side of the two-story brick wall visible as you drive down Ingleside.

“When the world is okay with having parties again, Macon’s Architect of Rock ‘n’ Roll will welcome you back with open arms,” wrote Brad Evans. Macon opened their arms – and wallets –right back, fully funding this project within 24 hours. The recently completed mural is stunning, a triumvirate of the superstar’s iconic looks through the years.

Despite his vocal appreciation for his hometown, Little Richard was not buried in Macon, a fact that breaks many music lovers’ hearts. Instead, he was laid to rest in Oakwood Cemetery, a property of Oakwood University, the historically black Seventh-Day Adventist university that was Richard’s alma mater. We’re sad, but grateful to have so many mementoes of him here in Macon still, and doubly grateful that our city was always on his mind.

“You can’t do without love. Without love, I ain’t had nothing. The secret of everything is love.”

Little Richard was a genius of many things, one being self-love. His public boasts were a joy to witness – a manic burst of captivating, half-rhyming patter, a barrage of nicknames and accolades he’d bestowed upon himself, then a wild-eyed, bemused stare as he gathered his audience in the palm of his hand and deployed one of his catchphrases: “I’m not conceited, I’m convinced!” Then he’d howl with laughter, absolutely owning every moment of air time he was given. If any other human behaved this way, it would be abhorrent. When Little Richard did it, it was beautiful.

Through his self-mythologizing, Little Richard shaped the way we viewed him. He grew up in an era when the world wanted nothing more than to extinguish his joy and self-esteem, but he refused to let that happen. He ensured his legacy would live on by creating a body of work so groundbreaking that its influence is almost immeasurable, and by proclaiming that legacy at every possible moment, never letting anyone take credit for what was rightfully his. And the fact that Macon was on his lips every time he spoke is his gift to us. We’re the origin story, we’re part of his great mythology, and by including us he encourages us to be our best, most authentic selves. He lifts us up alongside him to such miraculous, unlikely heights.