Reclaiming the right to diplomacy

With the creation of a formal ambassador position in 2019, Muscogee (Creek) Nation is asserting its legal right to advocate for its citizens as a sovereign nation.

Photography and story by Melissa Harmony Apel

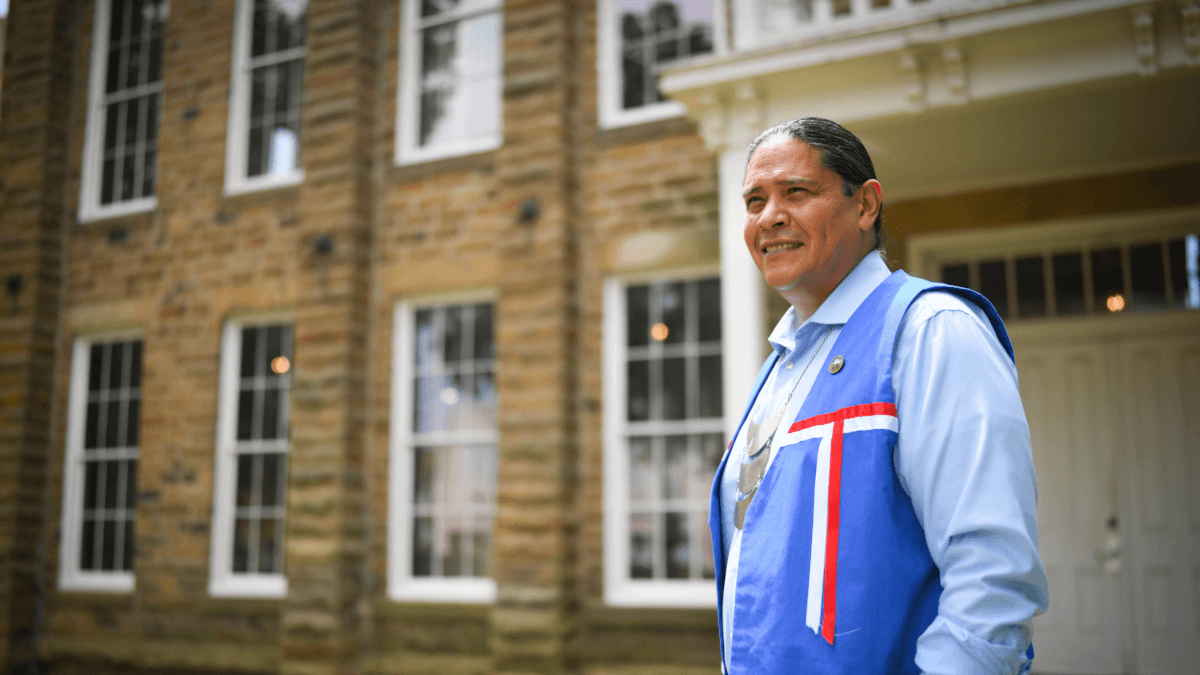

Jonodev Osceola Chaudhuri may be the first formally appointed Ambassador for Muscogee (Creek) Nation, but he’s quick to point out that his role is nothing new. “Emissaries or diplomats have been a part of our tribe’s history since time immemorial,” said Chaudhuri, whose ambassador position was created in 2019 by an act of Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s National Council with the Chief’s approval. “The diplomat function predates not just removal but European contact.”

MCN Ambassador Jonodev Chaudhuri at the Historic Muscogee (Creek) Nation Council House in downtown Okmulgee, Oklahoma. (Melissa Harmony Apel)

Based in Washington, D.C., Chaudhuri’s primary goal is to advance the policy positions of Muscogee (Creek) Nation leadership. That means testifying on the Nation’s behalf at hearings in the Senate and House of Representatives, holding meetings with congressional leadership, and coordinating with federal agencies. “If I’m doing my job, I’m hearing Chief’s voice, and I’m hearing the Council’s voice effectively and ensuring that voice is a part of conversations that can positively impact our citizens and really anyone who lives in our current or ancestral homelands.”

Chaudhuri’s role, now a part of the Nation’s formal laws, builds on the history of the tribe’s government-to-government international engagement.

Reclaiming the right

Today, Muscogee (Creek) Nation is one of very few tribal nations with a formal ambassador position, but historically, most tribes had special emissaries who performed specific functions when engaging with surrounding tribes, European powers, and later the American colonies. Chitto Harjo, an early 20th-century tribal leader and orator, served as emissary for the Nation to the U.S. federal government. Harjo traveled to Washington D.C. to speak to the Senate, advocating against the allotment of tribal lands in Oklahoma.

“A lot of that, unfortunately, fell off the map for Muscogee (Creek) Nation and other tribes when we were battling for basic existence,” Chaudhuri said, adding that when Muscogee (Creek) Nation was removed to Indian Territory, and Oklahoma became a U.S. state, there was a concerted effort to limit the tribe’s function as a true government, including the ability to elect its own leadership, and even doing away with the position of Principal Chief. The denial of rights to the tribe included any nation-to-nation diplomacy.

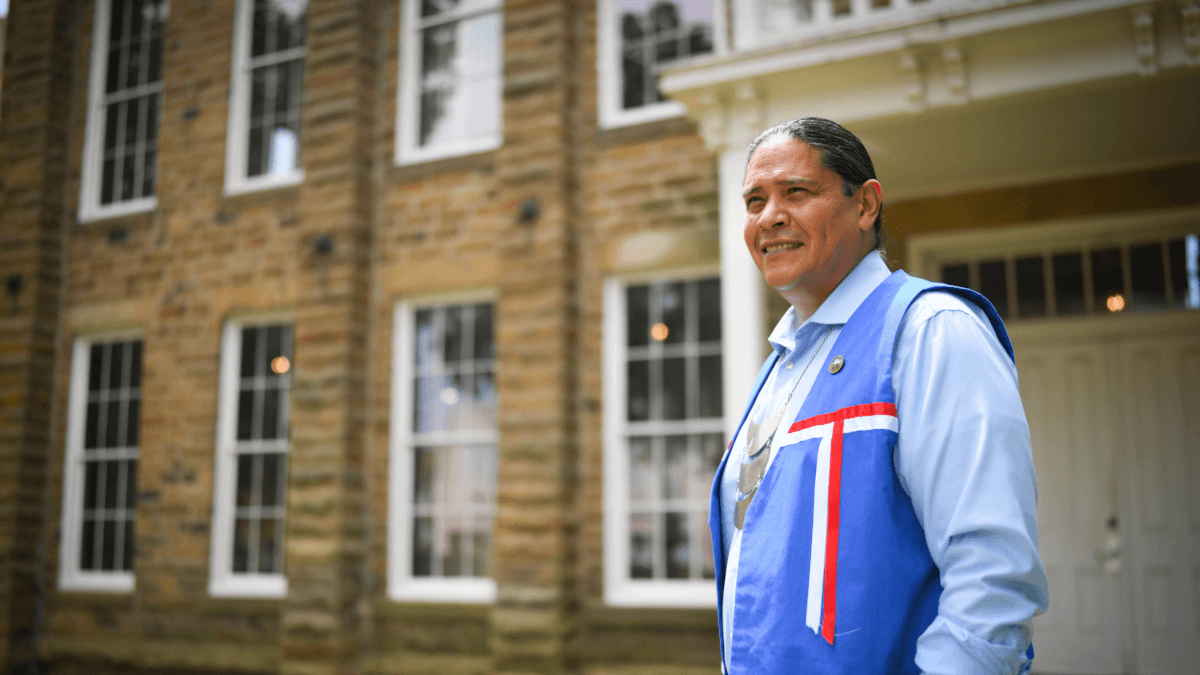

But with the creation of a formal ambassador position in 2019, the Nation is officially reclaiming its legal right as a sovereign nation to advocate for its people. “In this period of renewal and rebirth that Muscogee (Creek) Nation is in the midst of,” said Chaudhuri, “the creation of an ambassador who can perform those diplomatic functions flows from our historic sovereignty and our cultural traditions, through government.”

Ambassador Chaudhuri outside The Tribal Capitol Complex of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Okmulgee, Oklahoma (Melissa Harmony Apel)

A legacy of advocacy

Chaudhuri’s work builds on his family legacy of community service and advocacy. A former practicing attorney and tribal court judge, he says the only reason he went to law school was to hopefully serve as a “sidekick” to his mother, supporting her advocacy on behalf of Native communities and other underrepresented groups. Inspired by her parents who continuously fought to protect Muscogee (Creek) Nation sovereignty, Jean Hill was a relentless advocate and powerful orator. Among her many major achievements in Indian Country were the opening of one of the first Urban Indian healthcare clinics in the country, preserving Phoenix Indian School lands for public use in Arizona, and launching a prison counseling program for incarcerated Natives. “She was amazing,” said Chaudhuri of his mom, who passed away during his first year of law school. “There’s just all sorts of things she did to preserve human dignity among Native people and that was something that inspired me,” said Chaudhuri. “Growing up as a kid, I wanted to do my part to help.”

Chaudhuri’s path to Ambassador gave him an experiential arsenal that has proven crucial to his work. In 2012, Chaudhuri made the move to Washington, D.C. where he served in the U.S. Department of the Interior as Senior Counselor (a key advisor) to the Assistant Secretary of Tribal Affairs. From there, the U.S. Senate confirmed him as the Chair of the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC). NIGC is the chief federal regulator of the Indian gaming industry and oversees about 500 gaming facilities throughout Indian Country. A $38 billion industry, Indian Gaming is a major economic driver in Indian Country; Chaudhuri knew how crucial it was to get it right. But after nearly six years with NIGC, he felt drawn back to the Nation. “I think it’s pretty universal among Native people,” said Chaudhuri. “There’s a desire to serve your nation directly.”

McGirt v. Oklahoma

Having testified a number of times in before Congress, Chaudhuri knew federal relationships would be critical to his role as ambassador. But what he didn’t anticipate was the importance of his relationships with other tribal nations. And when Muscogee (Creek) Nation won the historic McGirt v. Oklahoma case in 2020, he found himself working with other tribes to raise awareness about just how the McGirt win would impact them.

The U.S. Supreme Court decided in McGirt v. Oklahoma that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation was never disestablished by Congress; therefore, prosecution of tribal citizens within the boundaries of the reservation fall under tribal and federal jurisdiction, rather than the jurisdiction of the state.

McGirt v. Oklahoma is recognized by legal scholars as the most significant Indian Country case decided in the Supreme Court in the last 100 years. As Justice Gorsuch passionately stated while delivering the majority opinion, “On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise … The federal government promised the Creek a reservation in perpetuity. Over time, Congress has diminished that reservation. It has sometimes restricted and other times expanded the Tribe’s authority. But Congress has never withdrawn the promised reservation. As a result, many of the arguments before us today follow a sadly familiar pattern. Yes, promises were made, but the price of keeping them has become too great, so now we should just cast a blind eye. We reject that thinking. If Congress wishes to withdraw its promises, it must say so.” This opinion made it clear that the case was not just about one issue in Indian Country, but rather the foundation of tribal authority itself – authority which was strongly affirmed. Immediately after the opinion came down, however, anti-sovereignty forces lined up to attempt to weaken or overturn the case.

“Part of my work has been supporting our leadership and not only directly preventing any undermining of that case,” said Chaudhuri, “but also educating and working with our allies to help folks understand why tribal sovereignty and strong tribal governments are good for everybody’s share of prosperity. By empowering tribal governments, better decisions can be made at the local level. Tribal nations develop policies to attract business into our communities and provide jobs, infrastructure, and public safety resources. When tribes succeed, everybody within their borders does as well.”

The McGirt case presented a variety of secondary issues regarding jurisdiction, including strengthening the tribe’s role as responsible environmental regulators and empowering themselves to prosecute criminals. “So public education around sovereignty and the McGirt case and building partners, both with other tribes and non-Native allies, is key to preventing bad policies from coming down the pike,” said Chaudhuri.

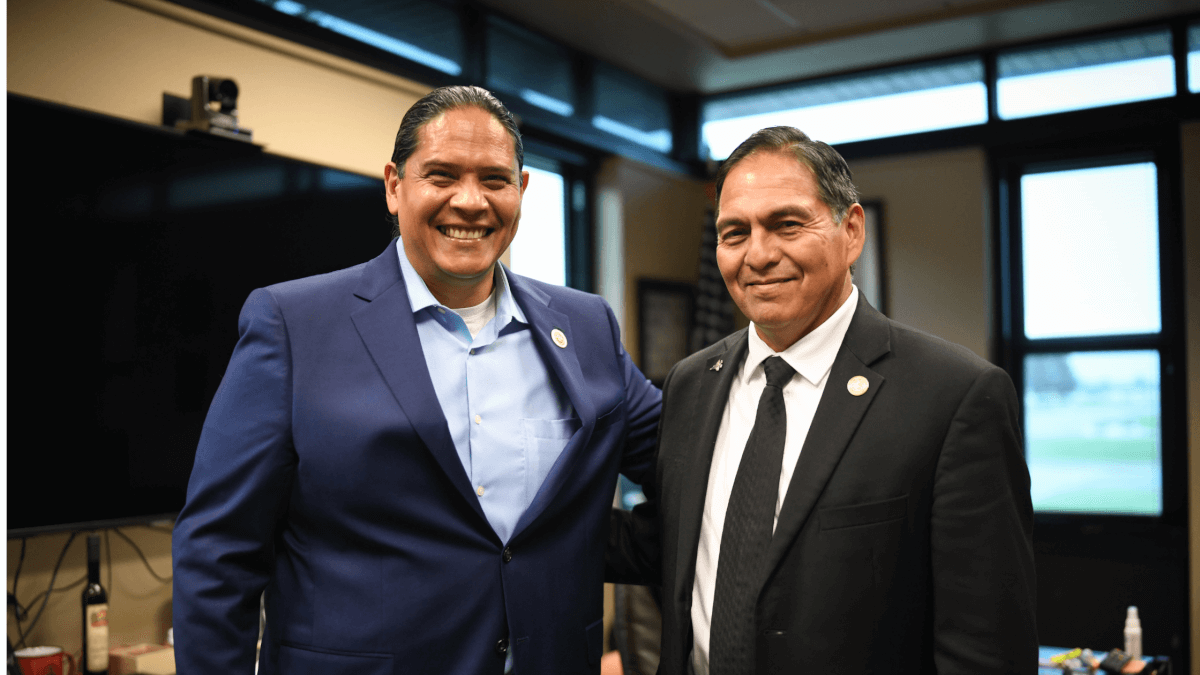

From top left: Chaudhuri at the MCN capitol in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. Chaudhuri meets with Principal Chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation David Hill at the Nation’s capitol. (Melissa Harmony Apel)

A bridge to Macon

Outside of sovereignty issues, as Ambassador for Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Chaudhuri is working with the city of Macon to establish national park protection for the Ocmulgee Mounds. He’s developing relationships with Macon leaders and with those “on the hill” in D.C. to ensure the preservation and protection of the tribe’s sacred sites. Chaudhuri says building relationships in the ancestral homelands is more than just window dressing. “Our relationship with Macon will continue to be based on education and understanding,” he said. “We’re building a kind of government-to-government relationship that is expanding on the public’s understanding of the history there, and telling the history in a constructive way, and I’m proud to be a part of that.”

Between the Nation’s work with Macon to establish a national park and building awareness around the McGirt case and the myriad issues involving sovereignty and tribal jurisdiction, Chaudhuri says when Muscogee (Creek) Nation speaks, people in Washington listen. “Our voice has power, but it’s taken some time to get there,” he said. Chaudhuri believes the Nation’s culture is its greatest asset for paving a path for the future, but inherent in that culture is strong humility and a resistance to touting its achievements. “That’s a good thing, and that’s who we are as a people,” said Chaudhuri. But in D.C., the most attention is given to the most recognizable groups who promote themselves. “Muscogee (Creek) Nation has never played that game,” Chaudhuri said. “We’ve always fought for sovereignty because we want to protect our culture, not because we’re trying to promote ourselves.”

With the national park in Macon on the horizon and public awareness around the McGirt case, the tribe has gained strength among policymakers. And that power and recognition came about in the best way possible, according to Chaudhuri, through humility and fighting the fight for the right reasons rather than self-promotion.

For Chaudhuri, his work is about helping Muscogee (Creek) Nation provide important services, provide opportunities for prosperity, and ensuring safety. The tribe developed great relationships in the Southeast that will help protect sacred sites and its original homeland. They’ve also fought, and will continue to fight, important legal and policy battles in Oklahoma.

“I’m excited to see where the Nation is going. By continuing a period of re-emergence, we can further exercise our sovereignty to improve the lives of not just Native people, but all people within our current and ancestral homelands.”