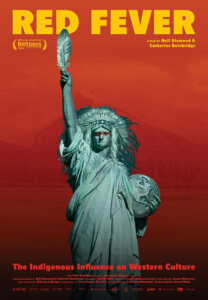

“Why do they love us so much?” Documentary directors Neil Diamond and Catherine Bainbridge discuss “Red Fever” ahead of its premiere at Macon Film Festival.

In this exclusive Q&A, the award-winning Québécois filmmakers behind Red Fever offer MM readers a sneak peek into the profound yet hidden Indigenous influence on Western culture.

Read on to learn the source of Red Fever’s humor and love, their key takeaways for Central Georgia audiences, and the inside scoop on their next surreal project.

By Sierra Stark Stevens

In the vein of their landmark film Reel Injun (2009), a documentary that tackled stereotypes of Indigenous people in Hollywood cinema and championed an emerging renaissance of Native filmmaking to the tune of three Gemini Awards and a Peabody Award, co-directors Neil Diamond and Catherine Bainbridge set out to make a movie about cultural appropriation. (Think: fans tomahawk-chopping at a Kansas City Chiefs game – or closer to home, an Atlanta Braves game – or music festivalgoers in faux-ceremonial headdresses).

Yet as filming unfolded, what the team uncovered was “the profound yet hidden Indigenous influence on Western culture,” Bainbridge tells MM. “I know that sounds huge, but that’s the truth of it.”

Many of the secrets showing the magnitude of that Indigenous influence, says Diamond, who is Cree, were “secrets so well-kept, they were hidden, even from us.”

Amid countless examples in the film’s 104 fly-by minutes, divided into four sections (fashion, sports, politics, and the environment) here are two hidden histories to whet your curiosity: The Founding Fathers found democracy, modeling fundamentals of the Constitution on the oldest participatory, federal democracy in existence, then and now – that of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. Footballers from Carlisle Indian Industrial School invented modern gameplay, throwing the first spiralized pass and crafting clever plays that would upend the sport with a defeat of top-dog Harvard in 1911, before one of those athletes, Jim Thorpe (Wa-Tho-Huk), would go on to be an Olympic gold medalist and the first president of the NFL.

Perhaps the most exceptional aspect of the film is the generosity behind its premise. Rather than (rightful) indignance, a mission to shame viewers for participating in this cultural heist, its guiding principle is curiosity. In his decades of travel as a journalist and filmmaker, Diamond saw countless instances of appropriation stemming from romanticized stereotypes that permeate pop culture, where people are powerfully drawn to a fantasy version of what Indigenous people are perceived to be, without any of the accountability for what the loss or depth those stereotypes hide. What Diamond asks isn’t, “What’s wrong with these people?” Instead, tongue in cheek as he speaks the opening voiceover, he asks, “Why do they love us so much?”

The wry, teasing Diamond invites viewers along on his journey of discovery, traveling thousands of miles across North American and Europe, interviewing dozens of scholars, artists, and activists, somehow maintaining an aura of love, openness, and humor while nevertheless speaking truth to power. Openness of that kind stems from confidence in your truth. Diamond states in in the film, “Our history and cultures are so rich that when people take the time to really get to know and understand us, they will see that the real thing is so much better than the fantasy.”

And you have the chance to be among the first to join Diamond on this journey of discovery, first in this pre-festival Q&A, and then on your own downtown’s silver screen.

Red Fever’s premiere, shown for the first time outside Canada, where it premiered at Hot Docs Film Festival, is August 15 at the Douglass Theatre Downtown Macon.

The film was selected as the opening night feature of the 19th annual Macon Film Festival (August 15-18), in partnership with Fire Starters Film Festival, which was launched in 2023 and showcases film and visual art made by Indigenous creators, with a particular emphasis on the Muscogee (Creek) experience, and in support of the initiative to designate the Ocmulgee Mounds as Georgia’s first National Park and Preserve.

Q&A with Neil Diamond and Catherine Bainbridge

Did the connection between Macon Film Festival, Fire Starters, and the Ocmulgee Mounds National Park and Preserve Initiative influence your choice of Macon as the site of your U.S. premiere? Did it feel like a natural partnership?

CB: It’s important to us to be connected to the community and great things going on. You have awesome things going on here.

ND: Yeah, because when we started out, we were very local.

CB: It wasn’t really until 2009, with Reel Injun, that we became more internationally-minded. Before that, we were mostly filming in Cree territory. So it’s exciting for us to connect to history that is shared by so many communities, like yours.

How did you begin working together?

ND: I met Catherine through her husband, Ernest, who I grew up with. I was studying photography in Montreal when I ran into Ernie at a powwow. As I was taking photographs, Ernie approached me with their first daughter in his arms. He said hello, and a couple of weeks later, he called me up and said, “We’re starting a magazine. Would you like to help out doing photography?” I said, “Sure.”

CB: We started a news and culture magazine together called The Nation, serving all the communities of James Bay. There wasn’t any written media and journalism in the community there at the time. It’s still going today, 30 years later, and we’re super proud of it. In Neil’s narration in Red Fever, you can see that kind of turn of phrase and comedic, wry tone. His writing was the same. Plus, he’s obviously visual and a photographer, so it was just a natural progression from storytelling in magazine form to documentary.

ND: Catherine had already been doing documentaries … But one morning I walked into The Nation office and Catherine said, “Would you like to direct a film?” I thought, “I’ve never done that before, but I’ve always wanted to.” So, I said “sure” again. From there, we started doing short documentaries for the Aboriginal People’s Television Network, and I don’t even know how many projects we’ve done together since.

Is “Red Fever” the biggest story you’ve told, the most far-reaching?

ND: It is, actually. We went to Alaska, Boston, New York, Paris, Germany …

CB: Kansas City, Utah, Arizona, British Columbia, and all over the Northeastern U.S. in Haudenosaunee territory.

It’s so funny, I don’t know if you noticed, but there is a medicine wheel kind of thing with the four directions and four sections of the film. Serendipitously, we shot the film in all four directions – north, south, east, and west of Quebec.

ND: Oh, yeah, that’s right. I went way north, above the Arctic Circle, to film the Inuit part of the story.

CB: For me, that was one of the most powerful stories in terms of making the point of why. Why make the movie? [The section referred to is about the Shaman’s Jacket. See the film.] At the beginning, the film was just about appropriation. It became about something much deeper.

This doctor friend of ours, a white gal, really cool, said to me once, “Look, white people just want to know what boxes to tick, what they’re supposed to do or not do. Just tell me the rules.” But then she said, “But I guess the truth of it is, if you can make people feel at their heart something, then they don’t need rules. They’ll know from their heart how to make decisions about all these things.”

In this story, you get it from the heart that A) these are spiritual designs and B) they were in a community where the spirituality of that culture was almost wiped out. You feel all of that through this story. It just said it. We didn’t have to wag our finger. You don’t want to shame anybody, but you let the story get to the heart of the matter.

I’m interested in how you are able to toe that line – to touch people’s hearts and make them feel connected – generate a sense of love and attachment – without letting people cling to a romanticized version. It’s easier, simpler to attach to a fantasy.

CB: Something I’ve learned from Neil, my husband, and Cree culture is to start from love and understanding. Cree culture is not a shaming culture. It’s a teasing culture.

So that’s really key, when you bring any kind of criticism to the table, to come from a place of love but at the same time be able to point out how complicated it is, where it can be really damaging, where it can be hurtful. If it comes from a place of shaming, people won’t open their hearts to listen.

You can hold people accountable and do it with love. You can have those two things.

ND: Another reason why we come to it that way, is that Ernie, I’m sure, and I have never been offended by people appropriating Native culture. And the reason is because our culture is still very strong. When we get together, we still speak in Cree. I would say about 95% of people still speak Cree. Little children walking around, they’re speaking in Cree. I have a brother who still lives off the land. In northern Quebec, residential schools started very late. My father never went. My mother went briefly. But the schools were located in the territories, in the villages.

CB: Everywhere else, like Carlisle Indian School in the film, it was those horrible, industrial things. Stealing people from their communities, children ripped away from their homes.

ND: So we don’t have that same sense of loss. I feel for a lot of people because they’ve lost so much. They’ve lost their land, their culture, their language. Their grandfathers don’t know how to speak the language.

CB: And so how Neil explained it is that you don’t even see yourself in those stereotyped images as a Native person anymore.

A key insight is that if Indigenous people are always portrayed in the past, that means there’s nothing contemporary for young kids to see of themselves. There’s nothing of today. It’s as if modern Indigenous people don’t exist. It’s a weird from of erasure.

Particularly in America, people have a hard time dealing with cultural and actual genocide, that it happened. If everything’s in the past, you don’t quite have to deal with that.

All the juxtapositions are what work without ever lecturing anybody. People can put it together themselves, in so many different ways. It’s up to their heart, their mind.

How did you choose what not to include? What other categories would you have included?

ND: When it was still going to be about just a cultural appropriation, there was music, especially Navajo music.

CB: Pretendians.

ND: Appropriating native spirituality – plastic shamans.

CB: We didn’t even touch food. Potatoes, tomatoes, chiles …

ND: Corn, chocolate …

CB: Apparently 70% of the world’s food originates from North, Central, and South America. Italian food without tomato? Forget it. And I’m Irish. We would have all died without the potato.

So, is there a food film coming down the line?

CB: No, but Neil, tell about the masks.

ND: We’re just finishing another doc. It came out of Red Fever, actually, kind of how Red Fever came out of Reel Injun.

When we were filming in the Pacific Northwest with the ‘Namgis, we learned that the Surrealists were heavily influenced by the Alaskan Yup’ik and Kwakiutl masks. Hitler considered the Surrealists’ art degenerate, so when the Nazis took over Paris, the artists fled to New York. They found all these masks in a New York shop that had been stolen or sold, and other objects, spoons and beautifully carved sculptures that inspired their art.

CB: They wrote and talked about it how it inspired them, but no one would listen because in a racist European mindset, it was primitive. It was not sophisticated. But when you hold the West Coast Indigenous art beside Surrealist works, you see the influence right away.

Now, what was once looked at as anthropology and not meaningful to European art is being seen as hugely influential, and that film that Neil directed is premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival this fall. It’s called So Surreal: Behind the Masks.

What do you hope MM readers take away from our discussion, or Macon Film Festival viewers take away from the film?

ND: We didn’t film in the Southeast, but there’s a mention in the politics section about first contact. The Europeans and the Native people on the East Coast had a lot of trading of ideas and goods before removal. I always thought about the idea of how Europeans were influenced by the idea of freedom when they first came over. It might have been very shocking to them that people didn’t have kings or queens. A man or a woman, well, especially women, had a lot more freedom. I always thought that idea of freedom must have been a huge influence on the thinking of the Europeans who settled where you are. The history is everywhere.

CB: I just hope that we’re all taking a look at our history. Indigenous people know their histories, and now everyone gets to learn so much more. If you don’t know what has happened on this land that we’re all on, you don’t know where you come from. Knowing more about our history and the foundations of everything here – maybe it can help us find another way out of the mess we’re in.

There are key takeaways in the democracy section and in the environment section for how people can help navigate our way forward.

As Gloria Steinem says in the film, “It’s the biggest example I can think of, of a less developed culture being valued over a more developed one.” People can look more closely at 30,000 years of Indigenous culture, over a thousand years of democracy. There might be a few answers to our problems. There might be other ways to look at the world, ourselves, and our relationship to the world.

IMAGES courtesy of Macon Film Festival:

1. A still from the politics section of the film: Haudenosaunee women singing.

2. Co-director Catherine Bainbridge

3. Red Fever film poster

4. Co-director Neil Diamond

Read more about Macon Film Festival in the August/September 2024 issue of Macon Magazine, on stands now.

Read more about Indigenous culture in Macon in these MM stories.

See you at the premiere? Get your tickets here.