Fanning the Flames

From left to right: photographers Harmony Apel and Mike Young, curator Tracie Revis, and photographer Matt Odom at the Bright City gallery opening of Fanning the Flames in Downtown Macon’s Second Street Lane. Photo by Leah Yetter.

Curatorial statement by Tracie Revis

In the bicentennial year, Macon has encouraged honest connections and conversations with its complex past. Fanning the Flames is an opportunity for Indigenous and Macon photographers to share a conversation through photographs. The four Macon photographers were paired with one of two Muscogee Creek photographers to create a theme and see where the conversation leads.

This project was an experiment in social change and public art. The participating photographers were asked to visit with their Muscogee mentor to capture an image that portrays what this past year of Indigenous history has meant to Macon. Upon completion, the photographers stated that they were forced to think “outside of the box” and think more about “celebration” of modern Indigenous life rather than the stereotypical image of a posed portrait in front of the Ocmulgee Mounds. Some realized that they did not know enough about the Indigenous people to know how to capture what was significant or how they could relate. However, seeing them beyond the landscape produced a more intimate experience.

The final product was that we are more alike than different. The conversations represented in this exhibit showcase shared values and culture around food, healing, individual expression, education, fashion, family, and passion. In the words of one of

our photographers, “This project brings forth the importance of community and intergenerational connection as a means of preservation of a culture and fulfilling the human experience. These connections … between elders and children nourish an evolving identity and transcend separation, location, and time.”

Mvto to those who pass through this exhibit to see us as your neighbors and friends and not just as historical people. We are still here, and we are still Indigenous. As human people, we are more alike than different if we choose to see that we are all connected.

Go see! The additional selections featured here are from the same project that resulted in Fanning the Flames, the latest show in the outdoor art exhibit, Bright City. A cooperative effort between Dashboard, NewTown Macon, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and local photographers, the Bright City initiative is in its fifth season of bringing a public art exhibit of large, illuminated photographs to Downtown Macon’s Second Street Lane between Poplar and Cherry Streets. Fanning the Flames features work by Muscogee (Creek) artists Harmony Apel and Victoria Tiger and Macon artists Diana Davenport, Matt Odom, Mike Young, and Sarah Lemon.

The conversations in this pairing show that our youth growing up, whether in an urban area or rural area, are all kids. They are Indigenous wherever they live, and raising them with their identity is an important part of growing up Indigenous.

TOP Harmony Apel, taken in LaVerne, California

Harmony Apel’s children learn their Yuchi language through young learner books made by their grandpa. The books allow them to learn while they are away in California so they can communicate when they return to their summer ceremonies in Oklahoma.

BOTTOM Victoria Tiger, taken in Okmulgee, Oklahoma.

The historic Creek Council House in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, was the place to set up their formal government with the House of Kings and the House of Warriors. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation had to buy back their own building and restore its story. Here, Victoria Tiger’s son plays with a relative in front of the Council House doors.

This conversation represents soul. People will show their heart when they put their soul into something. There is a common Indigenous belief that says that when a woman cooks, her spirit goes into her food. She can heal with her food, and heart should be pure when preparing a meal.

TOP Sarah Lemon, taken in Macon, Georgia.

The story of H&H is a tale as old as time. A place where the soul is fed with good food. Food is a medicine that can heal us all; how we share our meals with others is also a type of healing. “I just go from my heart and then put it into my cooking,” H&H General Manager Tangie Myers explained. “Macon got a lot of soul food, soulful roots. It’s so deep embedded in everybody’s history.”

BOTTOM Harmony Apel, taken in Pomona, California.

As a dancer and artist, Harmony moved to Los Angeles to follow her career goals; now, raising a family in a melting pot community, she has carved out her place with her own identity. In this self-portrait, she stands by a mural of an Indigenous woman in front of an urban background, but also surrounded by vibrant, nourishing fruit, wildflowers and healing herbs, and native butterflies who migrate back and forth between disparate homes to find a place that meets their needs in different seasons.

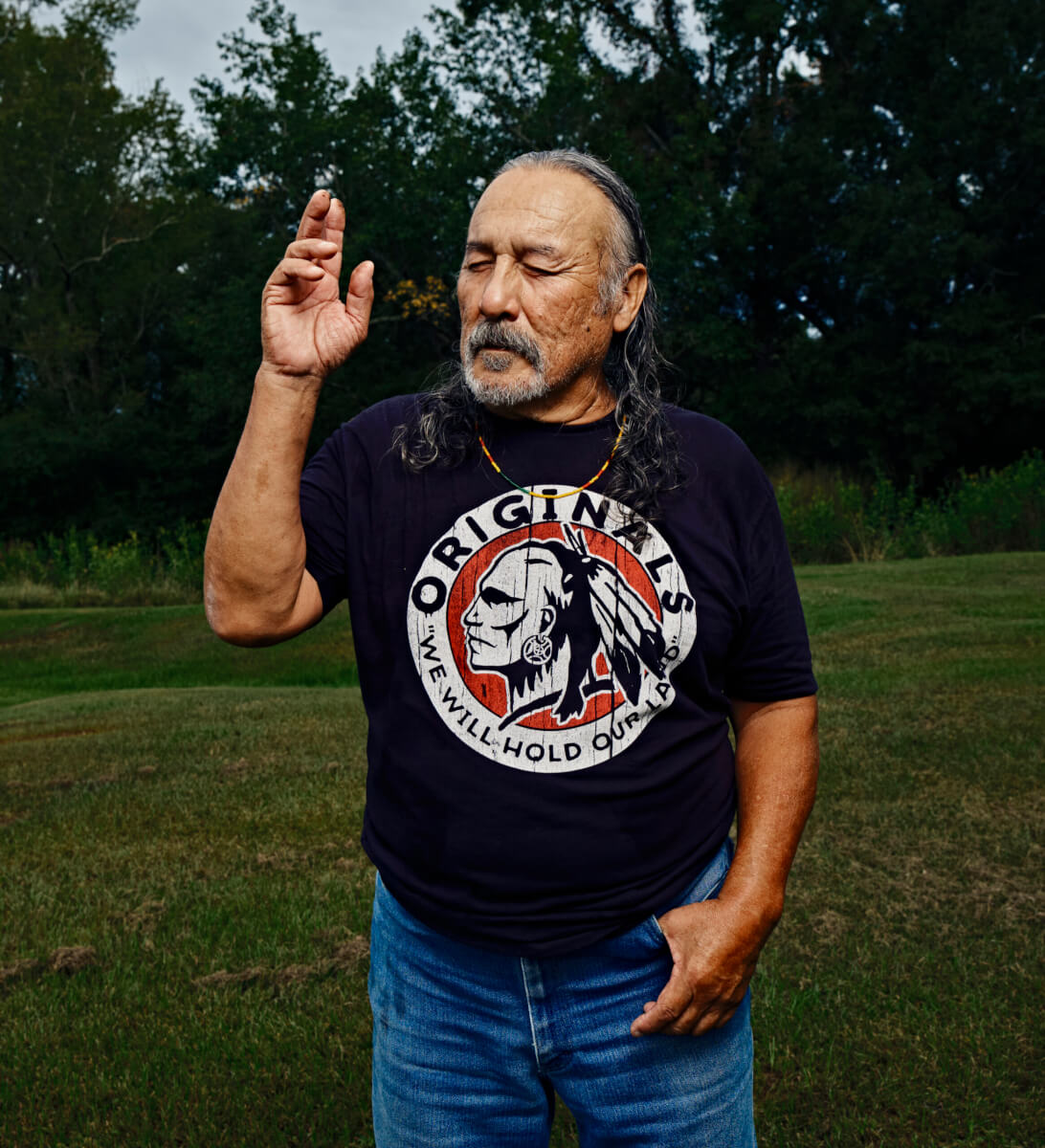

This conversation represents continuity. Culture survives as the people survive. When you take the traditional and mix it with the modern, each generation will put their stamp on it. It is how the language, the songs, the stories, and the people are still here today.

TOP Victoria Tiger, taken in Okmulgee, Oklahoma.

Buster Bear stands in front of his war pony on the road to Hickory Ground as a modern-day warrior. As a warrior and a veteran, he protects and defends his cultural ways and the land of this country

BOTTOM Mike Young, taken in Macon, Georgia.

Artist and flute maker Randy Kemp plays his flute along the Ocmulgee River at Amerson Park. While his attire is of modern influence, his flute and creativity come from the elements of nature.

This conversation represents the ways that our traditional culture has evolved over time, but still carries on.

TOP Victoria Tiger, taken in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The council oak tree in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the ancestral fires from the Muscogee (Creek) homelands are buried.

BOTTOM Diana Davenport, taken in Macon, Georgia.

The shellshaker at the Ocmulgee Indigenous Celebration is wearing milk can shakers. As culture evolves, women have adapted, and some dancers will wear a lighter shaker, and some continue to wear the traditional turtle shell shakers.

This conversation represents that our people are represented everywhere from coast to coast, and they are Indigenous every day, no matter where they are.

TOP Harmony Apel, taken in Long Beach, CA

Roxanne and her mom, Shirley, enjoy an afternoon in Long Beach. The family represents a second and third generation of Muscogee Creek families that were relocated to southern California during the federal relocation programs in the 1950s, where the goal was to break up tribal communities and encourage assimilation. Shirley recalls her mother and others getting together to speak the Muscogee language every day while the children played and the men went to work.

BOTTOM Matt Odom, taken in Macon, Georgia.

Wotko experiences natural medicine as he visits the Ocmulgee Mounds for the first time. The joy and excitement on his face are his natural reaction to experiencing this homeland for the first time.