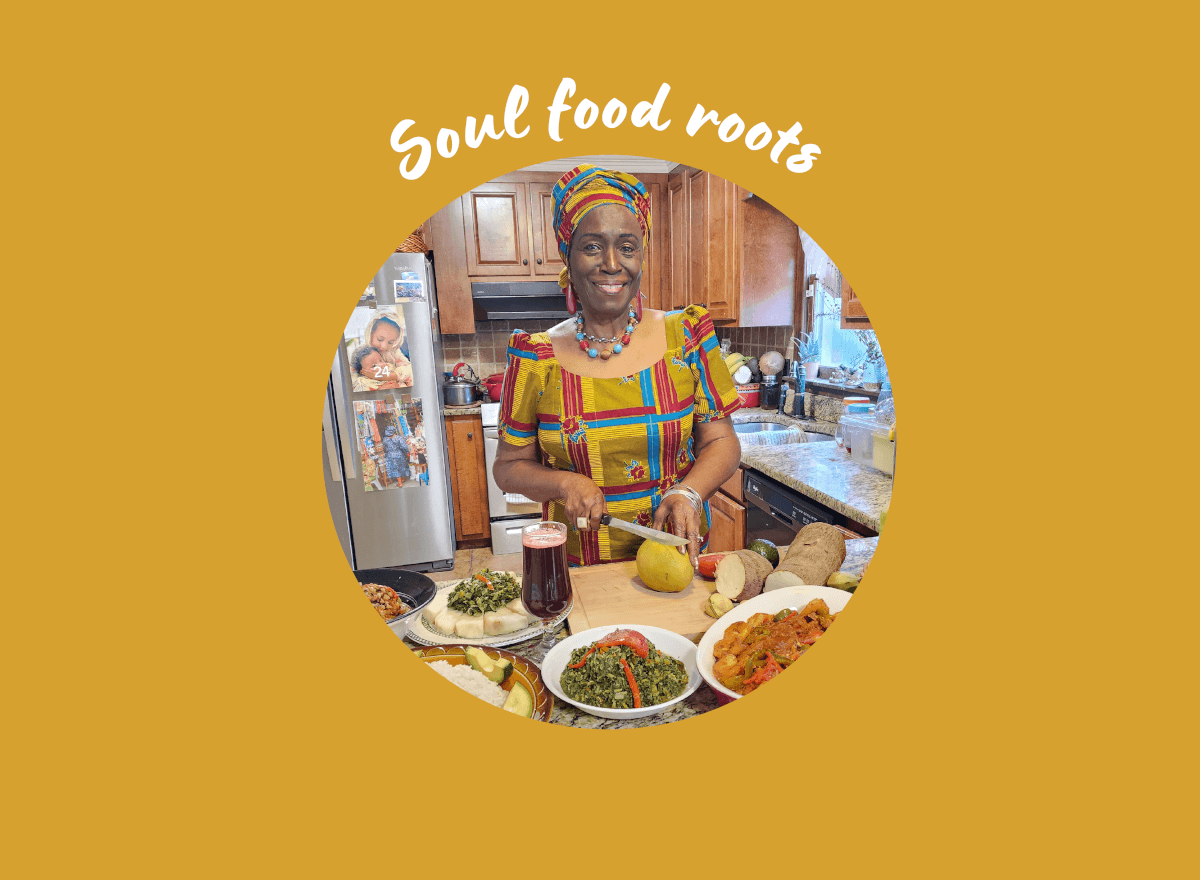

Soul food roots: West Africa in Central Georgia kitchens

Story by Clarence W. Thomas, Jr.

Cover image courtesy of Visionary Communications, Inc.

Soul food is a staple in the diets of most Southern Black Americans. But the beloved cuisine transcends centuries, cultures, classes, and continents as a comforting source of sustenance. Join us as we explore its origins and why some believe the African version of this “roots” food is next.

An active legacy

Fried chicken, rice, greens, black-eyed peas, candied yams. Salivating yet? Keep thinking on these soul food standards, and if you’re into them, you will. Ever thought about how they came about? Probably not. That’s because, like most food, we only consider the results – full bellies and satisfying feelings – and not the source. Especially if the food has unfamiliar and sometimes unsettling beginnings, as is the case with soul food.

The slave trade was an ugly episode in American history, but as repulsive as that period was, soul food is partly owed to it. Many of the items on today’s soul food menus were not from the Americas, although crops, like corn and sweet potato, of this land’s Indigenous peoples were incorporated. Items like rice and greens were loaded onto slave ships along with African people as a means of sustaining them during the arduous, often months long, journeys.

Africans used ingenuity and creativity to stay alive after arriving on American shores. In the absence of choice cuts of meat , they turned the often discarded portions of livestock (pigs, cows) like the head, tail, feet, and organs into dishes that were not only edible but palatable. The same could be said for carbs and veggies. Sweet potatoes replaced yam, cornbread filled in for fufu (a pounded-yam dough made for soaking up the liquid in dishes), as collards and turnips stood in for the leafy vegetables back home. Okra, of Ethiopian origin, was boiled or made into stews when it was not fried.

Rodney Mason, the founder of Restored Roots in Macon, considers soul food the ancestral food of Black people. Mason co-presents “A Jubilee,” an annual food education event designed to provide participants with empowering information that improves their lives and the environment. “Soul food is a manifestation of the things we as a people lost,” he added. “It fills in gaps in our history.”

As a public historian and dramaturg, Deitrah Taylor couldn’t agree more with Mason. The Central Georgia resident specializes in research that ensures that theatrical productions, documentaries, and films are historically accurate when they hit the stage or big screen. Her familiarity with soul food’s roots is partly owed to her upbringing.

Taylor is the descendant of a Gullah Geechee great-grandmother not far removed from slavery. She was partly raised by her grandmother, whose food, like the culture and language of the Gullah Geechee people, bears a striking resemblance to that of West Africans. As the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor’s website explains, they descend from West and Central Africans who were enslaved and brought to isolated plantations and sea and barrier islands in the coastal Southeast. In these secluded locales, they were able to retain many African traditions in food, the arts, and spirituality, resulting in a culture and new creole language, Gullah, that is wholly unique in the world.

Taylor is the descendant of a Gullah Geechee great-grandmother not far removed from slavery. She was partly raised by her grandmother, whose food, like the culture and language of the Gullah Geechee people, bears a striking resemblance to that of West Africans. As the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor’s website explains, they descend from West and Central Africans who were enslaved and brought to isolated plantations and sea and barrier islands in the coastal Southeast. In these secluded locales, they were able to retain many African traditions in food, the arts, and spirituality, resulting in a culture and new creole language, Gullah, that is wholly unique in the world.

Rice is especially prominent in the Gullah Geechee culture and sometimes paired with beans or peas. West Africans, the people whom many Gullah Geechee people descended from, were kidnapped and enslaved because of their skills in growing and harvesting rice. Okra and greens, including the leafy part of the rutabagas, provide vital nutrients to the Gullah Geechee. Finding the freshest available vegetables is essential. And seafood gumbo – a tasty concoction comprised of potatoes, onions, tomatoes, peppers, fish, and other items – mimics the stews and soups of West African countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

“Soul food is a connection to our past,” Taylor suggested when asked about the value of the traditional Southern food source. “These foods connect us to our ancestors. They’re an active legacy.”

On and at the tables of local West Africans

To confirm the similarities between tables donning soul food dishes and those of West Africans, I began with my next-door neighbor, Lizzie Ndubuisi, a veteran medical professional originally from Nigeria. The spry senior’s ability to go and do very well can be partly attributed to what’s on her table.

Because West African fare is rich in protein and carbohydrates, three full meals are not a necessity in her house, says the mother of four. Ndubuisi learned to cook from her mother and never lost her urge to eat fresh food. Growing up far from fast food, in a tradition-rich household, she rarely ate out.

Ndubuisi buys local every other year when returning to Nigeria, but Macon – and Atlanta – based shops sell what she’s used to in between trips home. “I’m not opposed to change, but my preference is to eat what I grew up with,” she says.

The results make for a healthier meal and person, she insists. While this is a departure from Western culture, there’s no mistaking the ties that bind soul food and Ndubuisi’s meals. She cites soul food items like mashed potatoes, okra, sweet potatoes, and various meats as being very similar to what she serves, such as jollof rice, okro or egusi soup, or plantains. Jollof rice, red rice’s big brother, gets its color from tomato paste and fresh tomatoes. Okra is the base for okra soup while melon seeds anchor egusi soup, which otherwise share the same content (seasonings, meats). Plantains are a larger first cousin to the banana and are usually fried.

Ndubuisi noted that soul food and West African dishes are both about providing comfort. Especially when eating greens and cornbread, in the case of soul food, and the West African duo of soup and fufu, with the hands. “Eating with your fingers makes it sweeter and better. There are so many similarities,” says Ndubuisi. “Black people here and back home are still the same. We still have something that makes us one.”

The traditional West African dinner that the author of this article enjoyed at Nigerian native Chi Ezekwueche’s home during the holidays was both familiar and foreign. The founder of the Tubman Museum’s annual Pan African Festival went all out. Gracing the table of her and her husband’s abode were fish stew with king fish as the dominant item, rice, mixed greens comprised of spinach and kale, black eyed peas, and yams. Bowls of chin chin (a crunchy, fried dough), avocado, and fruit (mango, tangerine) alongside a tall glass of hibiscus tea, rounded out the picturesque tabletop.

Attendees sample international cuisine at Jubilee: A Taste of Soul at the Tubman Museum. Photo courtesy of Dean Brown.

I didn’t know if she was finished or just getting started upon arriving. She was as busy creating ambiance as I entered the kitchen as she obviously had been creating the meal earlier. “In my country, food is not just for nourishing our bodies, but also for nourishing our communities. Food is about hospitality,” she said before referring to what I witnessed her doing as I walked in as “running around.”

Skipping lunch paid off and provided me ample room to sample every mentioned item. Chin chin has a similar taste and texture to animal crackers. They were all the better coupled with cashews. The kingfish, a deep-sea delicacy that has the trappings of tuna, and stew sauce, made a fantastic match for the rice. Loved the mixed greens! Seasoned to perfection and extremely fresh. I am not a black-eyed peas guy, but the hostess made it impossible not to dig in once I tried a forkful.

When asked about soul food and its relationship to West African prepared meals, Ezekwueche says 400-plus years of slavery didn’t break Black people’s connection to the Motherland. She recalled getting goosebumps in 1983, shortly after relocating to Macon with her family, brought on by a guest at her house dipping fufu into a soup with the skill set of a born and bred Nigerian.

The woman told Ezekwueche that she obtained her expertise eating cornbread and collards the same way. “You have to take your heritage and culture with you, or you won’t recognize yourself,” said Ezekwueche. “Bonds are never broken. The soul food is a manifestation of that.”

West African food: the next big thing

Who knew there was a West African cuisine takeout and delivery business in, of all places, Kathleen? Goes to show you that demand will bring about the supply. And much to our benefit, in the case of African Street Bites.

The Houston County home-based business is owned by 42-year-old Nigerian-born Oluwakemi “Kemi” Agbebi. For over twenty years, she has kept local bellies full of traditional items. Pepper, okro and egusi soup, jollof rice, and pounded yam are a few of the items on the menu.

Agbebi has customers from across the color and cultural spectrum, but the Black community drives the bulk of her business. “All my customers love my food. But a light switch goes off when Black people taste it. They describe it as soothing and satisfying,” Agbebi said.

Ezekwueche poses with friends at Jubilee: A Taste of Soul at the Tubman Museum in May 2023. Photo courtesy of Dean Brown.

She discovered the remarkable similarities between Southern fare and her homeland’s upon relocating to Central Georgia in 2003. In addition, she says her food is helping Westerners appreciate other aspects of West Africa, including art, music, dance, and fashion. “Soul food and West African food is definitely connected,” she said.

I must admit, upon tasting her specially prepared okro soup and pounded yam, I was taken in spirit to her country by the organic, fresh, perfectly seasoned soup, which took a couple of hours to prep. Agbebi says Africans don’t take shortcuts when cooking. “It’s prepared meticulously with love. It’s a full package. The result is bliss. Quality trumps everything,” she insists.

Agbebi, Ezekwueche, Mason, and Taylor all feel that soul food is here to stay. But African cuisine is next. As with soul food, its cousin from across the way will also transcend centuries, cultures, classes, and continents, due in part to people being better educated about international dishes and their willingness to try new things. Ezekwueche noted, “The language of food is the language of God and our ancestors. It transmits into warmth, love, and unity.”

African Street Bites Puff Puff Recipe

Prep Time: 10 minutes Rising Time: 1hour

Cook Time: 20 minutes Total Time: 1.5 hours

Ingredients for a serving of about 20 balls

• 1 cup warm milk

• ½ tsp. nutmeg

• ¼ cup granulated sugar

• 2½ tsp. instant dry yeast

• 1 cup warm water

• ½ tsp. salt

• Clear cooking oil of choice

Instructions

1. Pour water and milk into a large mixing bowl, add sugar and yeast, and mix well using a spatula until it dissolves. Leave to sit for 5 minutes.

2. Add flour, salt, and nutmeg, and mix together very well until the mixture becomes soft and stretchy. Cover with a plastic wrap and a clean kitchen towel, and leave unbothered for 1 hour until the dough rises and doubles in volume.

3. Pour clear cooking oil into a large pot and allow to heat up over medium heat. Drop a little batter in the oil. If it takes a little time to get to golden brown in color, this means the oil temperature is just right for frying.

4. Continue to drop golf-ball sized batter into the hot oil and cook until golden brown. Leave enough room between balls to fry without getting stuck together, and keep turning them over during frying. Ensure frying oil is at least 3-4 inches deep so dough can float easily and form beautiful round shapes. Also, turn down/off heat each time you are frying new batch and turn back on when new batch comes in so it cooks evenly.

5. When puff puff is ready and at desired shade of brown, remove from oil and transfer to a prepared plate lined with a paper towel for excess oil to be absorbed.

6. Serve warm with a sprinkle of granulated sugar as garnishment.

How to make Igbo/Naija bitter leaf/olugbu soup

By Lizzie Ndubuisi

Ingredients:

• Assorted meats, dried fish, crawfish, kpomo or dried cow skin, stock-fish

• Salt

• Peppers, Maggie, or knorr

• Egusi/melon seed

• Achi or thickener

• Cut bitter leaf or any vegetable of your choice.

Preparation

1. Steam together assorted meats and fish, stock fish, and other fish together in a pot with a little salt and pepper, plus spices, until soft.

2. Add 1-2 tablespoons of red palm oil to a skillet; warm the oil on a medium flame for 3 minutes; add ground egusi/melon seed to the oil and simmer for 8 minutes.

3. Add the steamed assorted meats to the skillet/pot. Add other ingredients/flavor of your choice: peppers, Maggie, and the olugbu leaf to simmer for 5 minutes on a medium flame.

You may consume the soup with farina, yam or potatoes.

Okro soup. Photo courtesy of African Street Bites.

On August 18, 2024, Restored Roots is hosting an educational event called “The Jubilee” at Emerson at Plum and Fall Line Brewing Co. Through cooking demos, tastings, and a visual art exhibition, the event aims to share the stories, techniques, and ancestral ingredients that underpin authentic African, Caribbean, Afro-Cuban, Gullah-Geechee, and more African American traditions like Southern soul food. With an eye toward food justice, there will be nutrition workshops and an outdoor market featuring the produce of local growers. Tickets will be available later this spring. Email rodney.mason@vitalfoodexchange.com for details.