Our Legacy: Knowing Better, Doing Better

A visit to Legacy Museum in Montgomery prompts action at home

By Sarah Gerwig-Moore

Photography by Jave Bjorkman

“Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

– “Strange Fruit,” music and lyrics by Abel Meeropol

In the mid-1800s, Montgomery, Ala., was a central hub of the U.S. slave trade. Thousands of enslaved people were sold at several auction houses throughout the city, and then sent farther on – to farm, build, tend and grow the Deep South.

Two hundred years later, the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law office working on constitutional challenges to capital punishment, prison conditions and mass incarceration, decided to educate the public about the historical roots of the problems it challenges in court.

Its study culminated – though it has not ended – with the opening of the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in spring 2018.

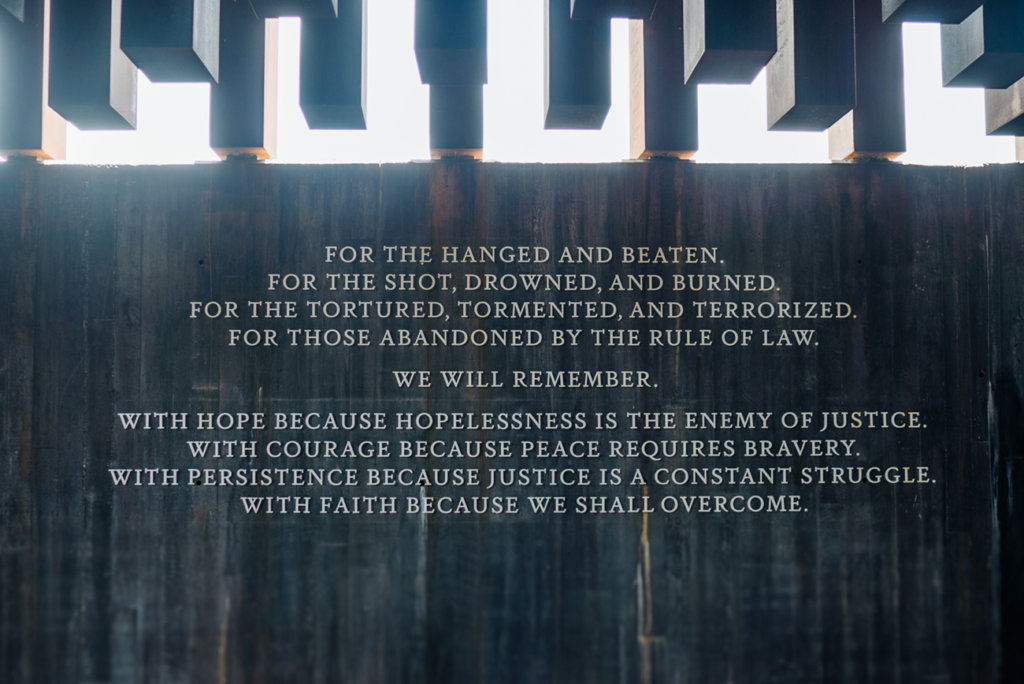

The impact of the museum and memorial are profound. Profound feels too small a word; they each evoke powerful physical and emotional responses: confusion, anger, sadness, sickness, a deep need to do something. Many visitors find the names of their family members or forebearers.

Visitors to the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, built inside a former warehouse that housed slave auctions, walk through interactive exhibits including ghostly projections of men, women and children housed in tiny cages, newspaper ads selling human beings with prices according to age and physical characteristics, jars of earth collected at sites of lynchings all over the country and business signs trumpeting segregationist policies. Video installations allow visitors to listen by prison phone with men and women facing death sentences. Touch screen computers display lynchings by state and county. Two small side rooms play video loops of programs featuring Civil Rights Movement work.

The corridor leading to the museum exit features displays raising a number of current concerns: the death penalty, prosecution of children as adults, treatment of prisoners. We are presented with perspectives, context and facts, but are called to think about the past that has led us directly into the present.

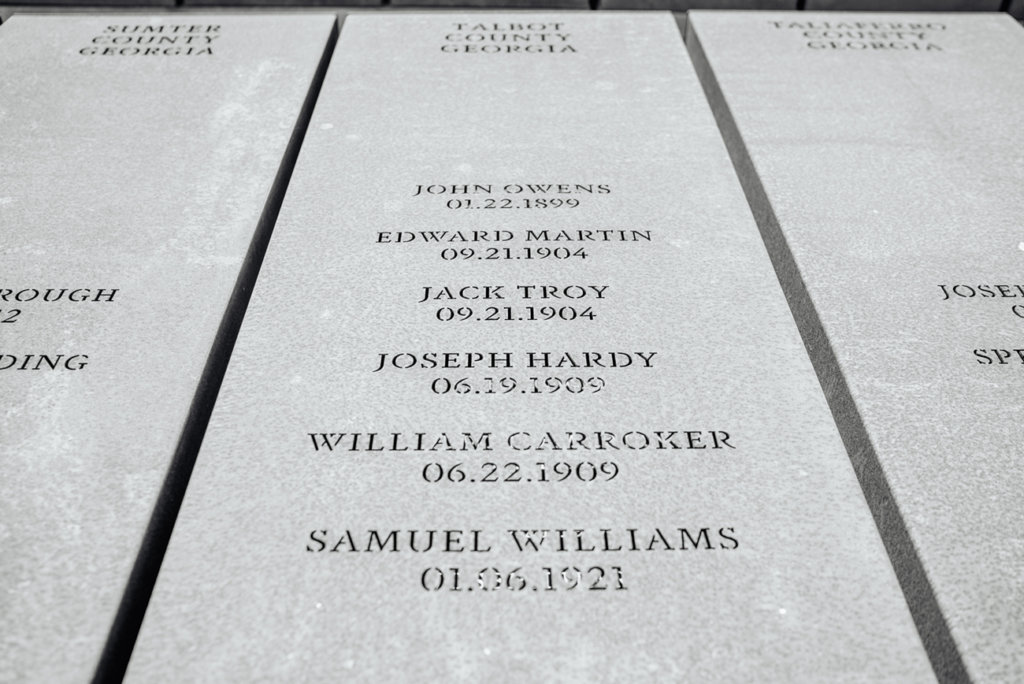

A little under a mile away from the museum, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates the lives taken in acts of violence and from whom justice – or even public acknowledgement – has been stolen. Museum staff have documented about 4,400 lynchings in the U.S. between 1877 and 1950. Every event was confirmed by two primary sources, which begs questions about how many more killings occurred but could not be documented through this meticulous procedure.

Visitors enter along a path of historical markers and intensely evocative sculpture and approach the primary space indirectly, along a grassy slope. At the first approach, the monuments – large corton steel markers for each U.S. county in which a lynching occurred – are at eye level. It is not an accident that, engraved with the names and dates of lynchings, they evoke coffins. As the path slopes down, markers are suspended from the ceiling, so we walk beside and then under the hanging representations of the many thousands of black bodies tortured and killed over decades of our nation’s history. Along the wall are markers with additional historical context:

For “annoying a white woman.”

For “helping to organize local sharecroppers.”

For voting.

The green space around the memorial includes, organized by state and county, a field of markers identical to those hanging inside the monument. Bibb County has a marker. It has six names on it of lives stolen with impunity: Tames Moore (8/12/1886), Willie Singleton (10/17/1890), Charles Gibson (9/12/1897), Charles Powell (2/04/1912), Paul Jones (11/03/1919) and John Glover (8/01/1922). Another is simply listed, along with a date of death, as “unknown.”

The markers are intended to be moved to and installed in the counties they represent, and in Macon much of this information is not new. Middle Georgia State University history professor Andrew Manis described much of it in his book, “Macon Black and White, an Unutterable Separation in the American Century.” Community members, led in large part by Dr. Catherine Meeks, oversaw the installation of a marker in honor of John Glover, killed by a mob in 1922, placed in front of the Douglass Theatre several years ago.

Building on the work that already has been done to learn and share local history, a number of community members are ready to take on the work of engagement to see the Bibb County marker installed locally.

Amber Jones, a recent graduate of Mercer University Law School who grew up in Macon, visited the EJI Memorial this past spring and returned with a commitment.

“Macon has a rich and powerful history,” Jones said. “I believe that we should embrace all our history. … How can we ignite progress without acknowledging our downfalls?”

Like so many others who have left the memorial feeling challenged, Jones added, “I am more aware now than I have ever been of the influence that our country’s history in lynching has on the current criminal justice system. I am excited to take an active part in bringing a piece of that memorial here to commemorate and honor those lost to lynching in Bibb County and to further educate our residents.”

There’s a process required here, and the logistics include engaging with the community to locate a site, secure funding and receive permits from the appropriate authorities (depending on the chosen site, either the consolidated government or Macon-Bibb Planning & Zoning Commission).

The EJI Monument Placement Initiative contemplates more than simply ordering a memorial and having it delivered to Georgia from Alabama. While volunteers have completed a Monument Retrieval Interest Form explaining why the monument should be brought to Bibb County, the application and placement procedures – along with estimates of pricing and shipping – are still being formulated by EJI. Cities also are encouraged to participate in the Community Remembrance Soil Collection and Historical Marker Projects to ensure “a process of community readiness” – perhaps the essential and challenging motivation for constructing the Memorial in the first place.

The drive to Montgomery is easy; on the drive home, we lose ourselves in reflection, our hearts heavier. It is impossible to experience the museum exhibits or walk among the memorials without terrible sadness and anger, but many visitors also leave feeling convicted to, in the words of Maya Angelou, “do better.”

This was by design, according to EJI Director Bryan Stevenson.

“Our nation’s history of racial injustice casts a shadow across the American landscape. … This shadow cannot be lifted until we shine the light of truth on the destructive violence that shaped our nation, traumatized people of color and compromised our commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice.”

Visits to the memorial should be booked in advance, and can be done so on the EJI website, museumandmemorial.eji.org. To join the effort to bring the Bibb County Memorial to Macon, email MemorialinMacon@gmail.com and watch for news of community meetings as the process moves forward.