Architecture to admire

Architecture to admire

A stroll through InTown Macon reveals a dozen architectural styles

By Jonathan Poston

Illustrations by Ric Thornton

By Jonathan Poston

Illustrations by Ric Thornton

The streets of Macon’s downtown feature a panoply of buildings in various American architectural styles from the 1820s to the present day. A pleasant 1.6 mile walk from lower Walnut Street to College Street and thence to the block where Macon Magazine is located on Washington Avenue, reveals the style and period details of 14 different structures and their unique histories.

While few buildings can be tied to one style alone, the selected examples best illustrate the characteristics of these important American architectural fashions. Here are brief stories and descriptions of each site to enliven this promenade. You should note that you will pass other examples in almost every style as you walk.

For further reference and definitions of certain terms, pick up a copy of the late Virginia Savage McAlester’s outstanding sourcebook, “A Field Guide to American Architecture,” and try your own hand – and eye – at determining the style and date of other buildings from Macon’s unique treasury of the built environment.

Macon Magazine intern Meghan Lindstrom gathered key research and provided invaluable editing assistance on this article. The author wishes to thank Macon historians Maryel Battin and Jim Barfield for providing their research and editorial comments, as well as Vera Mason Scherer and Rick Scherer for their help with the stories of 276 College St. Appreciation is also extended to Muriel Jackson with the Washington Memorial Library, Matt Chalfa and the staff of Historic Macon Foundation, Julie Groce, Nathan Corbitt, Jan Beeland, Robbie Beeland, Katherine Walden and Greg Barnard.

1: Federal/Regency

The Dr. Ambrose Baber House, 577 Walnut St., circa 1827-30, National Register of Historic Places

In the years after the American Revolution, building construction followed the earlier English style of Neoclassical, a movement inspired by the archaeological discoveries of Roman domestic architecture. Such design is variously referred to in this country as Federal or Adamesque, after its chief practitioner Robert Adam. Nonetheless, the style was transmitted to America and the coastal cities of the South through pattern books and immigrant builders trained in these forms. Late examples of a related, refined style are called Regency. The Regency movement came to Savannah primarily through works by the British architect William Jay.

Arguably Macon’s oldest in-situ example of sophisticated architectural design, 577 Walnut St., reflects the crosscurrents of the above styles and can be likened to contemporary examples in Savannah and Charleston of a true “Regency Villa.” Set within a large lot and upon a raised basement floor, the principal two levels of five bays are rigidly symmetrical with a central, projecting pavilion capped by a pediment. The house has lost most of its original interior fabric, especially its entry hall that boasted a pilastered archway and a stunning circular staircase.

The exterior stucco façade is largely original, having interspersed tie rods with molded caps (in Charleston called “earthquake bolts”), belt coursing above the basement floor and a semicircular inset for the front doorway. Certain features have been removed, notably the original open porch with its handsome masonry double staircase and wrought iron railing. The front portico and the wing on the west end were added during mid-20th century renovations. The low hipped roof is original in form and was once surmounted by a cupola or balustraded walk.

Virginian Dr. Ambrose Baber came to Macon by the early 1820s, setting up his medical practice and becoming a principal founder of Christ Episcopal Church across the street. Appointed as a diplomat to Italy by President John Tyler from 1841-44, his 1846 death resulted from accidentally ingesting cyanide after filling a patient prescription in error.

2: Gothic Revival

Christ Episcopal Church, 538-566 Walnut St., circa 1851, National Register of Historic Places

Serving the congregation of Macon’s first church organization, the current structure replaced a smaller wooden building from 1834. By 1840, Americans began to fully embrace the Gothic Revival style, especially for public and ecclesiastical buildings. This highly romantic architectural form, inspired by medieval castles and cathedrals, was already reaching its zenith in Victorian Britain, especially in church architecture and in notable public buildings such as the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. Gothic Revival remained influential for more than a century in various forms.

The construction of the church was supervised by James Ayres, Macon’s leading builder/contractor, responsible for the Lanier House Hotel, his brother Asher Ayres’ mansion, the Emerson building and (by tradition) the William B. Johnston (now Hay) House. As Johnston was a leading member of the church building committee, some have speculated that the designers of his house, the New York architectural firm of T. Thomas and Son, may have had some role in the plan for the church.

A few years earlier, the Thomas firm designed a similarly austere Gothic structure for the First Baptist Church in New Bern, North Carolina. Johnston paid for changes to the Christ Church plan at an early stage in order to add more pew space.

Christ Church boasts the traditional early 19th century Gothic elements: the steep principal roofline, a central square tower with a crenelated parapet, windows with lancet (pointed) arches and molded pinnacles capping buttress projections. The façade is stucco over brick, retaining its early finish with scoring – intended to make the church appear to be of stone construction.

Christ Church was probably the first building in Macon to possess stained or enameled glass windows. The front windows and those over the side doorways likely are original but others were added between 1870 and the 1940s. Jones Chapel, behind the church, was added in 1879 and the Gothic-style Parish Hall, connected by a cloistered hyphen, was built in 1926.

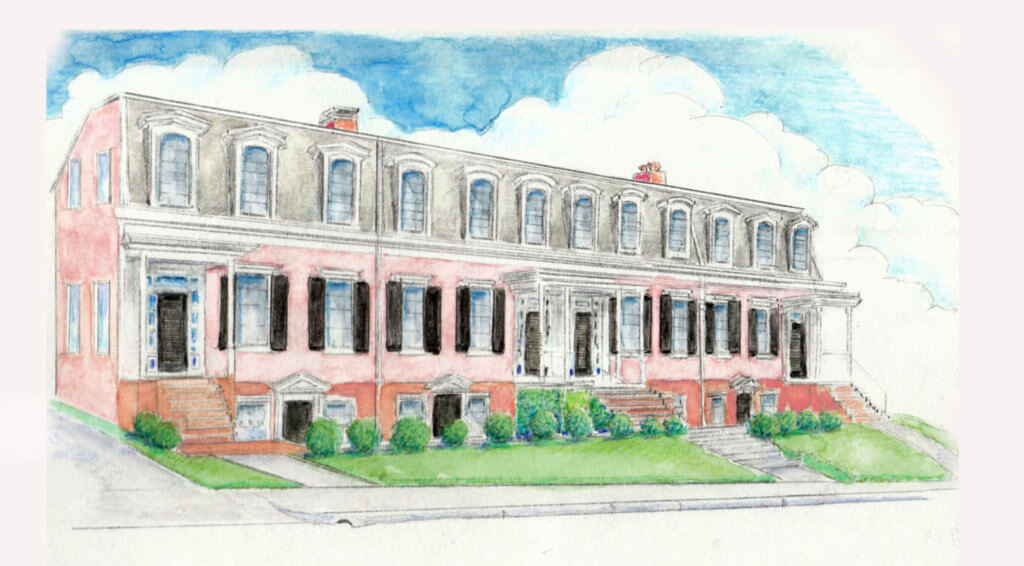

3: Late Federal/Second Empire Rowhouses

Ayres (Slate) Row, 931-945 Walnut St., circa 1855, National Register of Historic Places

Builder James Ayres erected Macon’s only remaining grouping of Antebellum row houses as a rental investment – with one set aside for his own use. His estate papers indicate these were finished just as he was undertaking the construction of the Johnston (Hay) House in 1855. The houses, with their English basements of stuccoed brick, their principal wood stories with tall six-over-six windows and the massive gambrel (two-sided mansard) roof, exhibit overtones of Federal, Classical Revival and Greek Revival in various elements, as well as a few details from the new Second Empire style.

Most of the facades of the four structures are original, including the window frames and sashes with period “wavy” glass, the rectilinear front doors shaded by simple Tuscan-columned porticoes, the stucco quoins, the weatherboard siding, the wide cornice that conceals a 22-inch gutter and, notably, the alternating pedimented and arched rooflines of the dormers.

James Ayres was born in New Jersey to an extended family of builders and followed his brother Asher, the city’s leading dry goods proprietor, to Macon. Ayres’ thriving building practice included two enslaved Africans, Primus Moore and Ben Jackson, specialty craftsmen in carpentry and plasterwork. After Emancipation, Moore continued in his own company as a leading tradesman.

Constructed in the model of the Anglo-American townhouse, each unit is divided by thick masonry walls from its neighbor and boasts ground floor rooms used as the kitchen and dining room, a front parlor and back parlor on its main level, and two bedchambers and a trunk room above. Separate necessary houses and possibly stables occupied the rears of each lot.

Evidence indicates that one or more of these houses were rented to tradesmen who worked on the Johnston project. After Ayres’ death, the McBurney family bought the row and these rental dwellings continued in the same usage until 1922, when a new owner altered the interiors, turning the grouping into a single apartment building that later acquired a notorious reputation.

In 1959, the dilapidated Ayres Row was acquired by four well-known Maconites, including an architect and two decorators, who restored the single character of each dwelling while carefully maintaining the important surviving features. Their joint rehabilitation of Ayres Row constituted the first major historic preservation project in Macon.

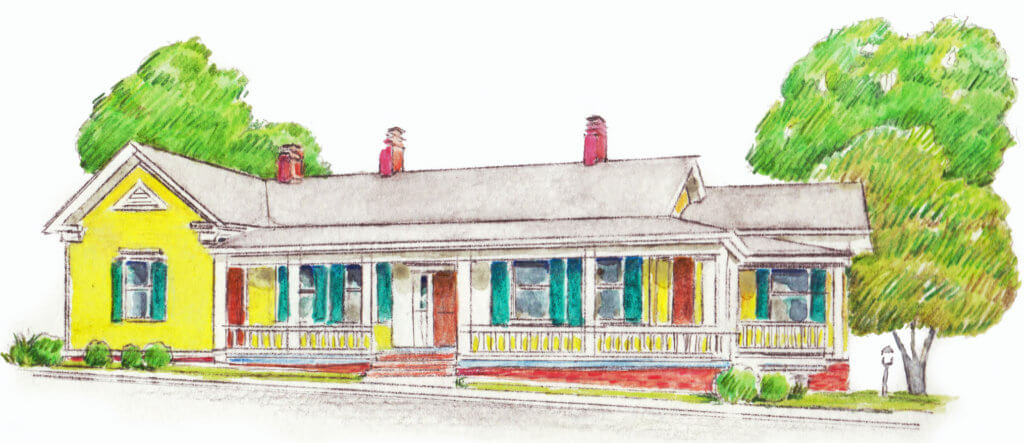

4: Macon Cottage

Burke-Henry House, 1027 Walnut St., 1860

While larger houses were the norm on lower Walnut Street, much of the upper end past Ayres Row was eventually characterized by smaller, single-story dwellings. The Rev. John W. Burke, a Methodist minister with a prosperous printing business, acquired this lot (then 1 acre) in 1859 and immediately began construction of a house with one principal floor of a central hall and four rooms, and a brick basement level below containing a kitchen, dining room and work rooms.

Greek Revival elements, such as the six-over-six windows and the rectilinear door architrave with sidelights and transom, combine with a front porch showing the influence of the Carpenter Gothic style in its jigsaw-cut square columns and balustrade. Later owners, the Robert Lamar Henry family, expanded the house with the addition of wings on either end in 1890.

When rehabilitated as an office and apartments in the late 1960s by leading architect Jackson Holliday and his wife, Cordelia, the Burke House was cited for its history and character as a Macon Cottage in an article on the project in the Macon Telegraph and News. The paper noted that the late architect/architectural historian Walter Hartridge of Savannah spoke in Macon at the organizational meeting of the Middle Georgia Historical Society in 1964 and first articulated the importance of this form. He stated that Macon had a “wonderful heritage” with its Greek Revival houses and small dwellings, adding that cottages of the 1870s and 1880s “formed the heart of Macon.”

Walking past Burke House toward College Street, one can see the stylistic evolution of the cottage form from vernacular Italianate examples to later vernacular versions of Victorian styles, such as Queen Anne and Eastlake, and eventually to Craftsman and Prairie types of the early 20th century.

5: Mediterranean/Italian Renaissance

Block-Coleman-Porter House, 245 College St., 1906

“Mediterranean” is a catch-all term that encompasses the late 19th and early 20th century eclectic architectural fashions of Italian Renaissance (not to be confused with the earlier Italianate), Mission and Spanish Revival styles. This exotic dwelling reflects the best of these crosscurrents.

Nicholas Block, president and later sole owner of the Dempsey Hotel – as well as head of the Central City Ice Manufacturing Company, National Milling Company, Massee and Felton Lumber Company, Acme Brewing Company and various banking interests – retained Macon architect Alexander Blair to design a new house for this key site facing the head of Bond Street. An earlier two-story wooden dwelling on the lot was moved to Garden Street in the Mill Hill area. Block’s wife came from Cincinnati, and he sent Blair to that city and to St. Louis to study Mediterranean architecture as it was emerging in their new suburbs.

This stuccoed brick house features a Ludowici tile roof, a deep cornice with bracketed eaves, applied ornaments of shields and torches, arched windows and doors, a central oval window set in a rococo frame, a side porte-cochere and marble steps leading up to a front square-columned porch – all typical of the Mediterranean style.

Ornamenting the front terraces, the deteriorated balusters, formerly of glazed terra cotta, have recently been replaced with stone balusters in the same profile. The spacious interior with oak and walnut paneling and other spectacular finishes boasts a basement with service areas, six rooms on each of the first two levels and a single large space on the third floor that served as a ballroom.

Sold in 1923 to Samuel T. Coleman II, founder of Cherokee Brick Company, and his wife, Edith Stetson Coleman, the residence became a boarding house after 1950 and was condemned by the city prior to its remarkable restoration by Mr. and Mrs. Ben Porter in the 1970s.

6: Italianate

Mead-Cubbedge-Willingham House, 261 College St., circa 1853-54

The Italianate style derived from the Picturesque movement that emphasized harmony between architecture and the landscape. In 1842, American horticulturalist A.J. Downing authored “Cottage Residences,” a popular volume illustrating ideal houses in Gothic and Italianate styles blending with the natural habitat.

This dwelling, with its substantial setback from the street, exhibits major features of the Italianate style: a pedimented gable centering on an asymmetrical façade of a projecting front section and a recessed section opposite, a second floor balcony over the arched front doorway, paired brackets supporting deep eaves, a low-pitched roof, paired two-over-two sash windows, a bay window on the rear of the south façade and two arcaded porches (loggias). Eventually though, the south end of the parcel was subdivided for the creation of two additional lots, thereby reducing the “rural” quality.

Henry Mead, brought by First Presbyterian Church to Macon to start a school and who played a major role in the start of the Georgia School for the Blind, acquired this site in the 1840s. Mead sold the property in 1854 to educator Sylvanus Bates for a price indicating that he had built the house. Bates, and possibly Mead, operated an Antebellum academy, the College Street School. After ownership by City Councilman John Jones, prominent banker-broker Richard W. Cubbedge purchased the building in the 1870s and lived here until his death in 1891. Osgood P Willingham, founder of Willingham Sash and Door Company, was the next owner. Willingham, whose family enjoyed the house for many years, made alterations including the removal of the loggias, the original door and the surmounting balcony.

After years of vacancy and neglect – and rumors that the dilapidated house was haunted – a local couple bought it and engaged architect J.L. Sibley Jennings to restore it. Jennings studied the structure and developed drawings for restoration with continued multi-family occupation. The house was sold, however, and the new owners, Gary Matthews and Dr. Barbara Matthews, engaged Macon historian Julie Groce as their consultant to assist them with a complete restoration as a single-family residence in 2003. The restoration received an award from Historic Macon in 2004.

7: Eastlake Style

McHatton-Wood-McGhee House, 275 College St., circa 1880-85

Charles Eastlake, a mid-19th century English architect and designer, inspired an artistic, yet restrained style of domestic building in England that eventually spread across the world. In America, the best-known examples in this mode are on the West Coast and generally of wood construction.

The brickwork of this house, the applied banding, the stone segmental arches of the window lintels and the Tudor-like gable featuring a strapwork band leading to a finial and a central sunburst feature, all hearken to the roots of this style in Arts and Crafts Period Britain. While the wrapping front porch with its thinly turned columns, jigsaw cut balustrade and pediment with a carved central ornament could also be features of a Queen Anne style house, the relative restraint, the flat surface of the body of the house and the predominating gable point to the concurrent Eastlake inspiration.

The son of a Louisiana secessionist who later become a sugar planter in Cuba, Dr. Henry Chinn McHatton was an important physician in late 19th century Macon. He married Eliza Hubbard of Connecticut while training at Bellevue Hospital in Brooklyn in 1880, and soon after the subsequent birth of their child, the couple moved to Georgia. McHatton had a distinguished career nationally and internationally and was the second chairman of Macon Hospital (now Navicent Health). At the time of his death, the Washington Post called him “one of the leading physicians and surgeons in the South.” Eliza McHatton was active in various medical and civic organizations while her husband actively pursued his avocation as an ornithologist. Their son Thomas H. McHatton, founding chairman of the Department of Horticulture and director of the Garden School at the University of Georgia, grew up in this house. Prior to his death, McHatton gave use of the house to the Red Cross for training of volunteers for service in World War I.

The house was divided into apartments before its 1980s restoration by architect J.L. Sibley Jennings for Dr. Perry Cohn.

8: Queen Anne

Duncan-Rosen-Scherer House, 276 College St., 1891

Characterized by its multi-tiered tower with its clerestory cap, slate roof, various balconies with latticework, bay windows and pedimented front porch with turned columns and corner pavilion, the Duncan House exemplifies a high quality of design in a Victorian style that began earlier in the American Northeast.

Derived from the work of British architect Richard Norman Shaw, houses of this type often include irregular plans and deliberately asymmetrical facades, yet they exhibit major craftmanship in their various elements.

The house was constructed for Caroline, the eldest daughter of William Butler and Anne Tracy Johnston, who had grown up in her family’s mansion on Georgia Avenue, and her husband, George Duncan, a South Carolina native with varied business ventures. With four small children, the Duncans needed their own residence, and construction presumably began after Johnston’s death in 1887 with funds from either the Johnston estate or perhaps from Anne Tracy Johnston herself. Period records indicate that Alexander Blair designed the house, or at least supervised its construction.

Following many years in multi-family use, the dwelling and garden have been gradually restored and enhanced – primarily through years of effort by the current owners Vera Mason Scherer and Rick Scherer. The Arts and Crafts-styled interior includes dramatic oak woodwork in its principal rooms, molded fireplace tiles and several stained-glass windows, such as the example in the dining room boasting a fanciful grouping of cherubs, possibly representing the four young Duncan children. Vera Scherer commented that her favorite features of the house include this window, which they have so lovingly restored. She also said she treasures interior details like the ornate, 3-inch brass cabinet key, the basket-weave detailing on the exterior front of the building and a cherub head with wings molded in terra cotta and incorporated at a high elevation into the brick chimney of the north façade.

9: Neoclassical Revival

Turpin-Grace-Hart-House, 340 College St., 1908

Even though Victorian styles predominated in America until 1900, new architectural fashions – inspired by the American Centennial Exposition of 1876, the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and by subsequent American passions for antiques and resurrecting the past – eventually became the norm. Colonial Revival began to emerge in the 1880s, and, soon after, the related but distinct Neoclassical Revival came in vogue.

Sometimes erroneously called Southern Colonial, Neoclassical Revival often featured pillared porticoes with correct classical proportions as well as other details, and it was in widespread use throughout America. Other typical features as illustrated by the Turpin House include the yellow brick construction, the hip roof, the deep cornice with modillions over the decorative frieze, the fluted-columned portico with terra cotta Corinthian capitals and the leaded glass front doors.

George Ralston Turpin, a prominent real estate and insurance broker, replaced an earlier house on this lot in 1908 with this very correct example of the style. He enjoyed it only briefly with his wife and family before his death in 1916.

Turpin was the son of George Balthazar Turpin, who was embroiled in lengthy litigation over the estate of a member of Macon’s wealthy Ralston family that went to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal. The case was for many years an oft-cited ruling on the issue of “undue influence” over control of property by a trustee on an infirm person. In this case, one of the properties involved was Ralston Hall, Macon’s theater. George B. Turpin prevailed in the suit.

Passing out of the Turpin family, first to the Walter Graces, the house subsequently became the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Freeman Hart. They hosted the organizational meeting of the Middle Georgia Historical Society (now Historic Macon) in the house in 1964.

10: Greek Revival

Nisbet-Huguenin-Proudfit House, 1261 Jefferson Terrace, circa 1844, National Register of Historic Places

Although Greek Revivalism had distinct English and European precedents, the growth of this style marked the emergence of a true American architecture. With the dissemination of the details through pattern books such as those of Asher Benjamin and Minard Lafever and with the travel of trained builders using its forms, Greek Revival permeated American domestic and public architecture for many decades.

The movement rested upon the view that the Greek temple was the most perfect of all of man’s architectural creations. This correct specimen exemplifies the style with its raised, two-story portico with fluted Doric columns supporting a large entablature including a cornice with dentil molding and a decorated frieze. The rectilinear entry door with a pilastered architrave, transom and sidelights on the first floor is nearly replicated above by a smaller opening with a projecting balcony. The wood siding on the front elevation is laid flush so that the house appears from a distance to possess a smooth façade of stuccoed masonry.

It is believed that Elias Carter, a Massachusetts architect who designed several buildings in Macon in this period, executed the plans for this house for Briggs Moultrie, but the dwelling was completed by subsequent owner James Nisbet. The inverted laurel crowns in the portico frieze match those seen on a similar house that Carter designed for the Napier family (now known as the Napier-Small House).

Edward Huguenin, born in Savannah in 1806, came with his parents and siblings to Middle Georgia during its expansion. With his second wife, Julia Fort, he amassed a large fortune from several cotton plantations worked by more than 300 enslaved Africans. Like certain other wealthy Antebellum Maconites, Huguenin preferred substantial town residences to extended living on their country plantations. Unable to serve in the Confederacy, Huguenin outfitted a rifle company that bore his name. His son, Edward Jr., became a successful farmer of cotton and pecans and developed Macon’s Huguenin Heights neighborhood.

11: Greek Revival – Cruciform design

Raines-Carmichael House, 1183 Georgia Ave., circa 1846-48, National Historic Landmark

Macon boasts a rare example of a cruciform house, directly derived from Macon’s leading 19th century architect from a published pattern of another American practitioner. Elam Alexander, whose prior works included the Cowles-Bond (Woodruff) House and Wesleyan College, took a plan from W.H. Ranlett’s design as published in 1846 in the most popular periodical of the day, Godey’s Lady Book (and later in Ranlett’s own 1849 pattern book, “The Architect”). Also used for an 1850s plantation house in North Carolina, this design for an “Anglo-Grecian Villa,” with additional Greek Revival detailing, adapted well to the prominent corner lot at Georgia Avenue and College Street.

Precisely because of the corner placement, the cruciform shape of the dwelling can be seen from several angles. The Ionic-columned, semi-circular portico on the south elevation is an alteration, as it originally followed the lines of the house between the wings instead of being curvilinear. Each of the points of the cross are comprised of three story wings, framed by full height Doric pilasters, also supporting full Grecian entablatures with dentilled cornices, pedimented gable ends and bay windows on the principal level.

The few changes to the ensemble, other than the porch, include a single-story addition on the northwest. While the exterior is in the form of a cross, the interior features an octagonal central hallway with a free flying circular stair rising through three floors. A cupola with a balustrade surmounts the house.

Built for Judge Cadwallader Raines, the dwelling was sold after his widow’s death in 1869 to John E. Jones, a president of the Central Bank of Georgia, whose relations the Millers acquired it thereafter. A business concern eyed this important corner site for a gasoline filling station, but it was saved from this fate and purchased by the Robert and Katherine Willingham Carmichael in 1942. Their daughter, Kitty Carmichael Oliver, became one of Macon’s leading preservationists and served as director of the Middle Georgia Historical Society for two decades.

This is one of only two individually listed National Historic Landmark buildings in Macon, so designated by the Department of the Interior, along with Hay House, for its significance to the nation.

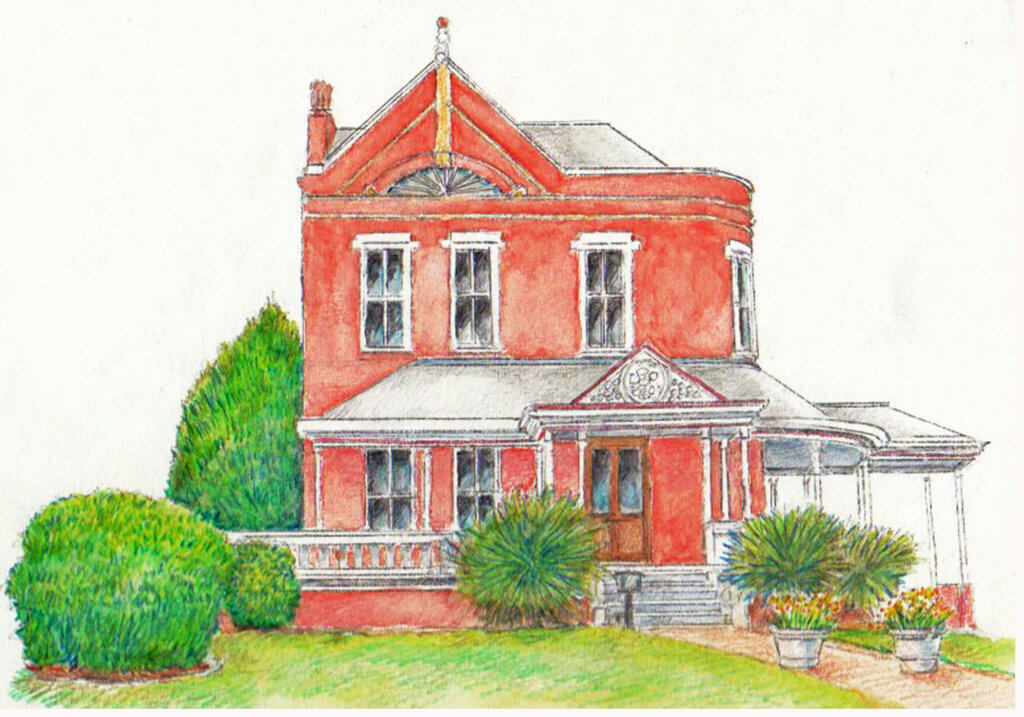

12: Second Empire

Hatcher-Groover-Schwartz House, 1144 Georgia Ave., 1880, National Register of Historic Places

A Marshallville planter, dairy farmer and businessman, Marshall James Hatcher constructed Macon’s purest domestic example of the Second Empire Style by 1880. Many Americans associate this style of architecture with the macabre, especially Halloween, due to the use of a house in this form in the works of cartoonist Charles Addams and in the resulting “Addams Family” television show.

Popular in Paris, this architecture arose during the reign of Napoleon III and hearkened back to French Renaissance forms. One of its most notable characteristics is the use of the mansard (dual pitched, four-sided) roof form attributed to 17th century architect Francois Mansart. Largely translated to America after the Civil War and during the administration of President Grant, it was the favored style for lavish public buildings such as the Old Executive Office building and the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the mode quickly caught on throughout the country for construction of both large and small houses.

Highlights of the detailing of this house that exemplify the period style include the brick façade with decorative stone banding and various tinted mortars, the corner multi-story tower, the mansard roof with colored and decoratively placed slates, the molded parapet at the top of the roof with modillions, the shaped dormers, the heavy bracketed cornice, the arched two-over-two windows with carved lintels and the lacy cast-iron front porch with its concave roof. This house exemplifies the fact that some Second Empire details match those of the Italianate style.

The house originally possessed a basement kitchen, but this function was relocated a few years later to a rear, wooden addition. Hatcher’s son, Judge Felton Hatcher, inherited the house. His family sold it in 1935 to the Denmark Groover family and in 1967, the dwelling became the property of the Bert and Edith Schwartz. For the last two decades, Rob and Heather Evans have owned this magnificent dwelling.

13: Beaux Arts

Washington Memorial Library, 1180 Washington Ave., 1916

Ellen Washington Bellamy provided $50,000 and this property for the construction of the Washington Library honoring her brother, Hugh Vernon Washington. Their father, James Henry Russell Washington, was born in Wilkes County in 1809. As a planter and businessman, he rose to be mayor of Milledgeville and then later, of Macon. He married his first cousin, Mary Hammond from South Carolina.

The family’s large wooden dwelling, the Washington McCook House, formerly stood on this site. At first shifted to face College Street on the western end of the lot, the house was eventually moved to Park Place by InTown Macon to save it from demolition in the expansion of the library.

The original section of the Library building was designed by J. Elliott Dunwody Jr., a 1914 graduate of Georgia Tech and a founder of the Macon architectural firm of Nisbet, Brown and Dunwody (still in operation today). Named for the Ecole des Beaux Artes in Paris where many American architects and designers of the late 19th and early 20th century trained, the resulting buildings of this movement generally follow Renaissance Classical inspiration but with exuberant and deliberately elaborate ornamentation that would not be seen in the European precedents. Symmetrical facades and smooth wall surfaces of stone decorated with ornate brackets, swags, panels, plaques and cartouches, with arched windows, columns and flat or invisible roofs often distinguish this architecture. Perfect for monumental and public buildings, Beaux Arts design, sometimes called Beaux Arts Classical, also characterizes other Macon landmarks such as the William A. Bootle Federal Building and U.S Courthouse (1905) and the Terminal Station (1916).

In the case of the original library as designed by Dunwody, the principal Washington Avenue elevation boasts an engaged portico with ionic columns and an entry architrave of marble details featuring the Washington family coat of arms within its broken pediment and a frieze ornamented by swags of laurel leaf garland. Although originally approached by a stone staircase with flanking bronze torcheres, this entrance was closed when the new addition of 1979 altered the library’s orientation and to some degree, its architectural purity. Large windows with arched transoms, square Doric pilasters surmounted by shields from the Washington coat of arms, a frieze with various carvings of attributes such as “Literature” and “Science,” (these were partially blocked by the addition of 1959), and a tall parapet further complete the Beaux Arts character of the Library.

Ellen Washington Bellamy, who was inordinately proud of her lineage, told a friend that she went to the building site after dark and placed her family Bible with its important records into the cornerstone before it was sealed.

14: Late (High Victorian) Gothic Revival

Holsey Temple CME Church, 1011 Washington Ave., 1895

The congregation of this church began worshipping as a part of First Methodist Church (now Mulberry Street Methodist) in 1839 while most members were enslaved people. In 1867, the newly independent congregation was organized and the current parcel was purchased with financial help from the Mulberry Street congregation. The original 1870 building on the site was destroyed by fire in 1895, and this structure was erected thereafter.

The CME church was organized in 1870 to create a separate African-American denomination out of the Methodist Episcopal Church South. The Macon congregation named the church, as did others in the emerging denomination in Georgia and elsewhere, after CME Bishop Lucius Holsey, a former slave who co-founded Payne College in Augusta and established Holsey Institute in Cordele.

Architecturally, the current church of 1890 is derived from a later phase of the Gothic Revival, often called High Victorian Gothic as opposed to the simpler, earlier and more symmetrical style seen at Christ Episcopal Church. The English designer John Ruskin popularized this mode, deriving a more ornamented approach based on European Gothic models, especially those of Normandy and Venice.

This building is asymmetrical in form with two differing towers on opposite ends, as opposed to a single steeple: one terminates in a crenellated parapet and the other possesses a four-sided peaked roof. The deep red brick exterior exhibits the best characteristics of this fashion with heavy structural detailing and decoration embedded in the masonry, such as basketweave patterning on the east tower and channeling in the buttresses. While most of the windows on the towers and the sides of the nave are lancet-arched, the front entry is surmounted by a group of rounded arched windows and a bullseye window beneath a stepped gable parapet. On the interior, the bracketed wooden ceiling, stained glass, pipe organ and pews are original.

A few doors to the east stands the Washington Avenue Presbyterian Church, also in Late Gothic style, which began in 1838 as a congregation of enslaved people worshipping together at First Presbyterian Church and is considered to be the oldest African-American church in Georgia. These two remarkable religious buildings, along with many others in this section of Macon, comprise a major part of Macon’s historic community of faith.