Macon’s legendary behind-the-scenes band leader

By Clarence W. Thomas Jr.

Photography by Dsto Moore

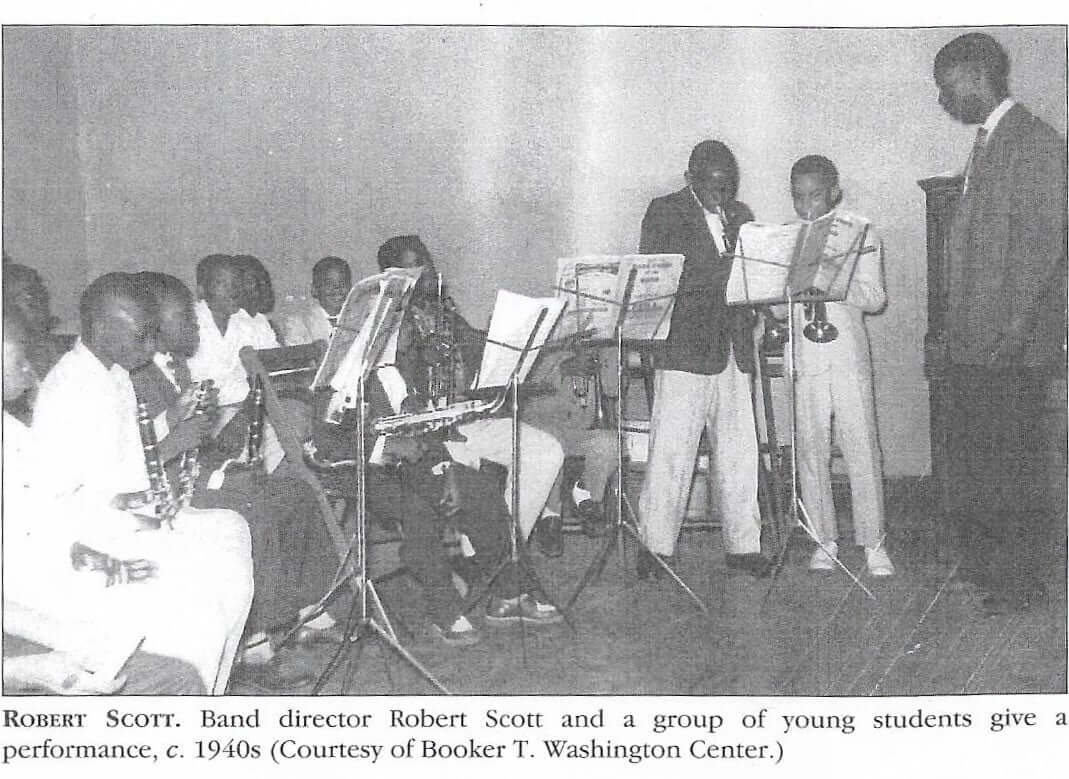

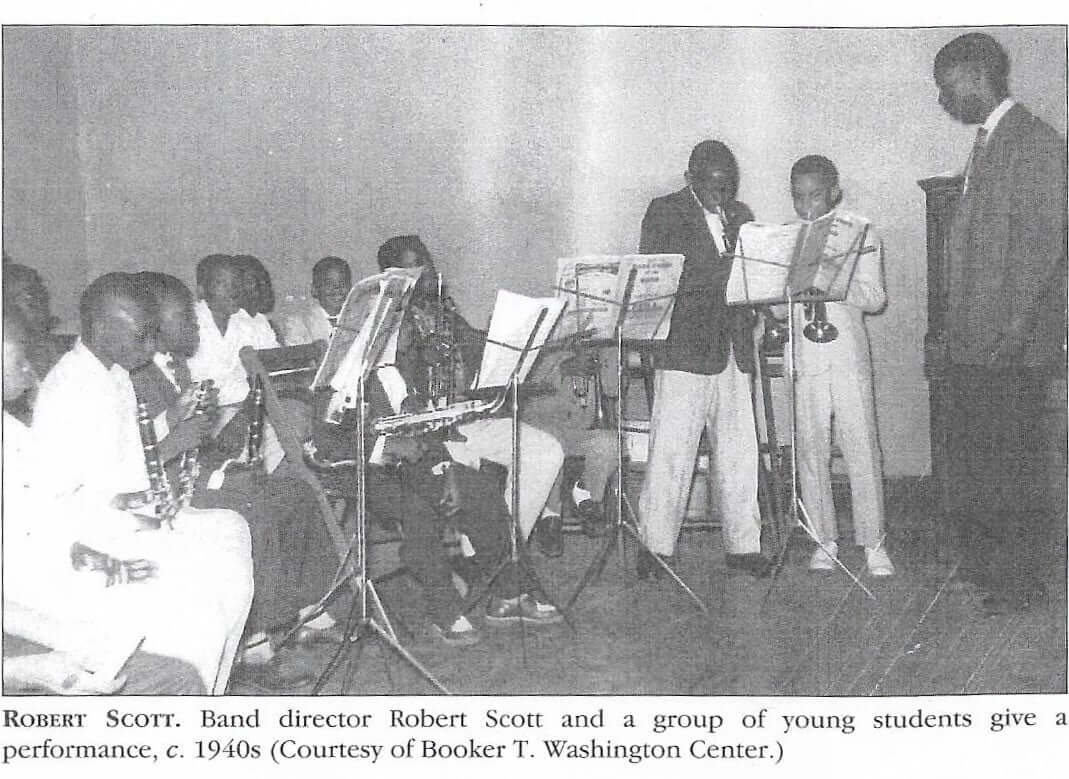

When we marvel at the hit makers in the music industry, there is a tendency to overlook those who laid the foundation for their success. Macon is a hotbed of past and present entertainment sensations, and one man, at one school from 1956 – 1970, taught and produced a succession of talent backed up some of the biggest legends in the business. The legacy of the late, great Robert Louis Scott, Jr., band director at Ballard Hudson High School, leads to over 30 students who went on to superstardom as musicians, producers, composers, percussionists, vocalists—and the list plays on and on and on.

The world is familiar with Macon music legends Little Richard and Otis Redding and locally developed acts like the Allman Brothers, Wet Willie and Marshall Tucker Band, as well as the this city influenced the likes of James Brown, Buddy Guy and Jimi Hendrix landing on the map of music lovers.

But what about the unsung heroes who set them up for greatness? While he wasn’t responsible for directly catapulting the careers of those mentioned previously, no person in Macon history planted seeds of musical success more often than Robert L. Scott, Jr.

Born in Macon on August 31, 1933, Scott used his passion and gift to lift students bitten by the music bug to higher heights. He was a music instructor and band director of Ballard Hudson High School, the city’s first Black high school bandleader. And despite this happening primarily during segregation, Scott created an iconic, formidable marching music force in Macon.

Overtime, Scott was a trusted source of talent for the music business, even establishing an office downtown near the future headquarters of Redwal Music Company, the booking and management agency of Redding and brothers Phil and Alan Walden.

Ballard Hudson was formed in 1949 as Macon’s only high school for ninth through 12th graders available to Black residents. Some students that attended gravitated to the band because of their love for music but also because of the mastery of music that Scott possessed.

One of those students was Newton Collier. Collier played trumpet at the height of his career with Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Percy Sledge and other renowned outfits. He and Scott were both residents of Tindall Fields (Heights). Scott first became Collier’s music teacher and later his bandleader at Ballard Hudson.

Another star student was the late bassist Calvin Arline, most known for his arrangements on the 1970s R&B supergroup The Manhattan’s hit “Kiss & Say Goodbye.” He co-wrote “We Got to Get Our Things Together” for the Dells, later covered by The Soul Children. Arline also played with Bobby Womack, Percy Sledge, Santana and recorded with Cher.

Critically acclaimed classical bass baritone opera singer Allan Evans, honored posthumously in March 2022 by Macon Mayor Lester Miller, was also taught by Scott.

Other performers who started with Scott and would go on to make careers out of music include Clarence Roddie (who played for the Pinetoppers and Sam and Dave), Charles Burns, Gary Lester (who backed up Percy Sledge), Sammy Dixon, Clarence Lucas Dudley Wisdom (all horn players for Arthur Conley), Danny Miller (who teamed with Joe Simon), Donald Veville of Brick, jazz keyboardist Tommy Goodwin, drummer John Morgan and singer Bo Ponder.

According to Collier, Scott was an unassuming, demure, slender fellow with a mellow demeanor – until he hit the classroom. There, he became a man possessed with perfection. Collier and others from the neighborhood worked with Scott after school in a feeder program for Ballard Hudson’s band.

“He loved music and could play all kinds of instruments. He knew something about what he was doing. I was impressed with him and really appreciate what he done for me,” Collier said.

Gifted is how Collier also describes Scott. He had a knack for tone and was very disciplined. He imparted those talents on Collier and others, instilling the ability to open ears up and listen for the sound of the music mixing with the room. Collier said that the lessons he learned in Scott’s class were with him while on the road as a professional musician.

Solomon Mims, a retired professional living in Macon who played in Ballard Hudson’s band in the early 1960s, is also a gifted musician because of Scott. He fondly recalled his first encounter with the band as a youngster, where his neighborhood, in which the school sat, was one of the band’s proving grounds. Mims would join scores of people as the band played during mock parades through the community, prepping for what would soon be a spirited performance in Macon’s annual Christmas Parade.

The practice sessions would lead to Mims playing French horn in the band later while attending Ballard Hudson. It would later serve as a means of Mims playing flugelhorn as a walk on for the Tennessee A&I State University band in Nashville.

He said Scott’s greatness is attributable to the creative freedom he gave his music students, along with discipline and the dedication to their craft he instilled in them. Mims still holds his band boss in high regards. “It was a great honor to play in that band,” he emotionally shared. “Mr. Scott instilled confidence in me and made me feel special by choosing me to play for the Ballard Hudson Tigers Marching Band.”

Scott’s skills transcended time, even after his passing on June 9, 2011.

Phillis Habersham Malone owns the 50-year-old Habersham Records store on Montpelier Avenue in West Central Macon. She, too, was a Ballard Hudson student and reminds residents that some of Scott’s protégées played for R&B hit makers Bobby Womack and Joe Tex, as well as fusion music sensation Carlos Santana. “He produced a lot of professional musicians. He knew his craft very well,” Habersham shared. “People need to know about him, especially young people.”

In 1968, Lillie Gantt Evans opened M.A. Evans Academy, an independent school in the historic Unionville neighborhood that still thrives today. Gantt Evans was intentional in crafting a balanced daily experience for students. That experience includes a band program, inspired by Scott, that is still in practice today. “He needs to be remembered as one of Macon’s outstanding music directors,” she said.

Scott’s impact on Collier was so great, in fact, that when he returned to Macon after playing on the road, he would seek out Scott to share in his success and catch up on what was happening locally.

“The learning never stopped with him,” said Collier fondly reflecting on Scott. “He wanted the best for his students and to make sure they were on note in the band and beyond.”

Even from the beyond, Scott’s impact can still be heard in the music. Before his passing, he told writer and “Music from Macon” author Candice Dyer, “I never made a lot of money or enjoyed the fame of some of my students, but there are other ways to make a difference.”