A thousand miles to rediscover our history

Efforts around the world help reignite interest in one of Macon’s greatest stories during our bicentennial year

By Michael W. Pannell

The streets are familiar to us, routine really: Mulberry, Cotton, Fifth, Poplar. These are streets we walk on to grab a coffee, enjoy a meal, or see a show with friends and family. But on a December morning in 1848, these streets were anything but routine for married couple Ellen and William Craft. Carefully navigating toward Macon’s train station before the city stirred awake, the Crafts felt terror, alongside the almost unimaginable hope, driving them on.

Ellen and William were enslaved, and it was illegal for them to roam freely. Being discovered where they weren’t supposed to be would have meant serious, torturous reprisal. If it was thought that they were traveling because they were trying to escape, it likely meant death. On that winter morning, just days before Christmas, the Crafts were doing just that.

You’ve heard of escaped-enslaved-person-turned-abolitionist Harriet Tubman, one of the most famous figures in American history. Her name adorns the Tubman Museum of African-American art, history, and culture at the end of Macon’s Cherry Street. You’ve also likely heard of Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth. But what about Ellen and William Craft? According to modern scholars, their descendants, and a growing number of authors and filmmakers, the Crafts were engaged in the most dramatic and widely known escape of their day. In their time, they were internationally famous because of it. The Crafts, little known by locals now, were Macon’s own. They lived not so far down the street from you. That is, until the day they set out for freedom.

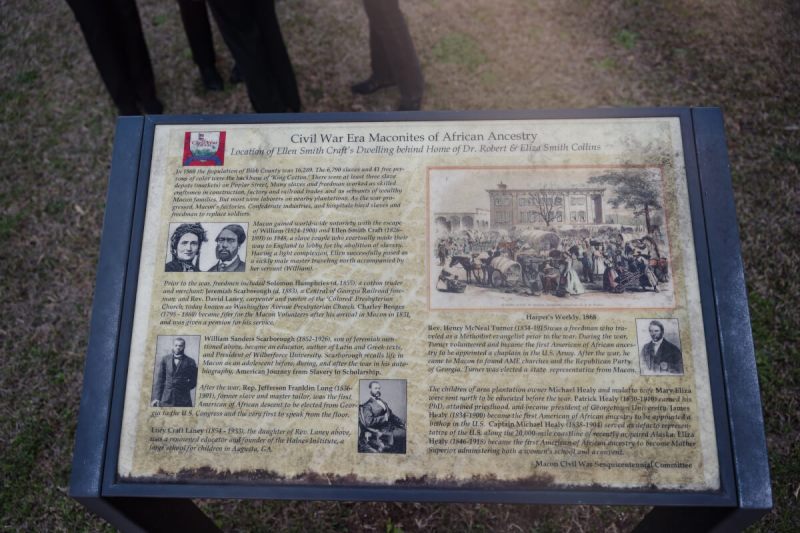

“There’s certainly renewed interest in our great-great-grandparents,” said Julia-Ellen Craft Davis, who carries her great-great-grandmother’s name. Davis, her sister Vicki Davis Williams, and cousin Gail DeCosta — all hailing from Charleston, South Carolina — were in Macon in February as part of Macon200’s Bicentennial Lecture Series. They spoke at Wesleyan College, in area schools, and at the Cannonball House. Coincidentally, the Cannonball House is just two doors down from 830 Mulberry St., the mansion where Ellen was enslaved. It was from there that she and William set out in predawn darkness, hoping to reach safe haven in Philadelphia.

They traveled by train, steamship, and stagecoach. But how could they do that without getting caught?

Ellen was the mixed-race daughter of an enslaved Black woman, Maria, and her white enslaver, James Smith. Smith was a well-known citizen of Clinton, Georgia, just north of Macon in modern day Jones County. The rape of Maria, a tragically common occurrence during slavery, meant that Ellen appeared light-skinned. At times, she was mistaken for one of the Smith children, a fact that angered Smith’s wife.

At age 11, Ellen was gifted to Smith’s daughter Eliza upon the latter’s marriage to Robert Collins. The three relocated to Macon at the Mulberry address.

Captive by different enslavers, Ellen and William were skilled workers — she a seamstress in the Collins household who lived in a cottage to the rear of the house, and he the enslaved apprentice of a cabinetmaker living downtown. Though prized for their skills, they nonetheless suffered multiple injustices, including the trauma of family members torn from them through sale and the violent whims of their enslavers.

It was illegal for slaves to learn to read or write in Georgia or for any white person to teach them. Ellen and William desired education, but that paled in comparison to their wish to be free. They didn’t want to have a child born into slavery, subject to being dragged from their loving arms.

Because Ellen was light-skinned, their plan was to disguise her as a sickly white man with masculine clothing, shaded glasses, short hair, and a face partially covered with a poultice. William would travel as her attending enslaved man. It was a brilliant plan, but not without grave risk.

It’s the stuff adventure stories are made of, and in fact two films are in the works. One is in long-term pre-production with a Craft descendent as consultant, and another titled Everlasting Yea! is close to completion. According to Variety, it will star Juliana Canfield as Ellen and Jovan Adepo as William. A documentary from Savanah College of Art and Design (SCAD), A Thousand Miles and Counting, has already been made and can be viewed on SCAD’s website.

However, the details of their travels to Philadelphia, Boston, Canada, England, and subsequent return to the United States is best told in two books. The first is a slim volume written by Ellen and William themselves while in England called Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. The second is a new, historically rich telling of their tale by Ilyon Woo. It’s called Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom and was published by Simon & Schuster in January. Woo’s in-depth research and skillful storytelling make it the cornerstone of the current rediscovery of the Crafts.

“Growing up, we had pictures of Ellen and William in our home along with their children and other relatives — they were all just part of our lives,” said the Crafts’ descendent Davis. “Our grandmother wanted to make sure we knew about them and told us their story. Then, when I was in college, she gave us all copies of Ellen and William’s book when it was reissued after being out of print for so many years. I suppose that’s when the significance really, really hit me. It made me all the more proud of them. We all felt that.”

Woo holds a BA in the Humanities from Yale and a Ph.D. in English from Columbia. Among the book’s accolades is being described as “superbly researched and masterfully written” by Library Journal. She has told the Craft story at countless events and through the media, including C-SPAN, which created a detailed online lesson plan based on her work.

Davis said Woo’s scholarly research on her great-great-grandparents, and the people and places surrounding them, allowed her to make connections and expand on what she already knew from family stories such as: how was Ellen able to navigate certain towns where they traveled? Woo found records showing one of the Collins children was born in Charleston, a town the Crafts had to carefully circumnavigate.

Or, why did Ellen and William choose that particular day and year to escape? Woo examined financial problems Collins faced, showing the sale of Ellen was a real and imminent possibility. Additionally, enslavers were more predisposed during the Christmas season to give enslaved people days off, even passes to travel, which made their timing a now-or-never affair.

In rediscovering the historic but very human Crafts, Woo and the Craft descendants became friends. Woo recently invited them to a Manhattan celebration of the book, describing meeting the extended Craft family as, “a tremendous honor and pleasure, for which I’m grateful beyond words.”

Woo said, “No one knows the Crafts as they do, and each has lived and interpreted the legacy of their ancestors with such wisdom and grace. In the presence of these great-great-granddaughters of the Crafts, who have so generously shared their family archives and stories, I felt myself especially attuned to Ellen Craft in new ways.”

With Woo being the leading Craft expert, one might wonder what has moved her the most. “Reading and learning of Ellen and William Craft’s childhood experiences moved me deeply,” she said. “Meeting descendants of the Crafts at William Craft’s gravesite in Charleston is a moment I cherish in the present — one I will never forget.”

While in Macon in February at the Cannonball House, relatives walked the few steps down Mulberry to the former Collins residence. Where Ellen’s cottage once stood is now parking and an alleyway. They also met with Muriel Jackson, historian and head of Washington Memorial Library’s Genealogical and Historical Room. She showed them artifacts and an era-correct map, enabling them to outline Ellen and William’s likely routes to the train station. The group also made their first-ever trip to Clinton to see what’s believed to have been the Smith home.

“It was fascinating for us to see where they started in Macon,” Williams said, “to see where they lived and the 1848 map of Macon. In Clinton, we took pictures of the house and imagined small slave houses where Ellen and her mom and other slaves might have lived. I thought about how Ellen was emotionally abused by her master’s wife. My son’s oldest daughter is almost 11, and I can’t imagine her going off, away from her mother like Ellen was forced to.

“Ilyon’s book made their story more alive for me. … I’m proud, so thankful, and so blessed they persevered and had the gumption to do what they did. They kept their children from slavery, shined a light on slavery’s ills, and later in life, they helped others through their work, the schools they started, and in many other ways.”

Part of the Craft descendants’ ongoing reconnection with their heritage has meant trips to England, where Ellen and William’s children were born into freedom. Though some distant cousins they met had not been aware of their enslaved forbearers, Davis said all the reunions have been warm and welcoming.

But what’s such history to us modern Maconites, those of us who aren’t directly related to the Crafts? Reading the books and hearing the speakers does bring the story home. But what do we make of it?

The Craft’s great-great-grandchildren were invited to Macon in February through the efforts of retired dentist Thomas Duval. Duval grew up in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood, attended Howard University, and after a successful practice, served as Georgia’s first African American state dental public health director. He also has had connections to the state correctional system. In retirement he has become an avid educator, especially for children, about Macon’s African-American history. He is co-chair of Macon’s Bicentennial History Committee and has created a children’s Black history coloring book, including the Crafts’ story.

Duval said he believes there is so much Macon residents can learn from Ellen and William: “The more we learn about them and understand the past, the more kindness and goodwill we can choose to have for one another across all boundaries. We can reach that ‘beloved community’ where all are safe and secure and have wonderful relationships with one another. Even in England, the Crafts could have very well said, ‘We’re set, we’ve got ours,’ and left it at that. But no, they wanted to return home to help others even though it meant facing further difficulties, discrimination, and injustices in the post-Civil War South. They returned and were lied about and taken advantage of. Theirs is a wonderful American story, though their lives didn’t have a Hollywood-perfect ending. Really, it’s better than a Hollywood ending because their legacy, the good they did, is lasting and real in people’s lives, including their descendants.”

Duval especially hopes African American and historically underserved children are inspired by the Craft’s story in seeing themselves in such real, heroic characters.

“In so many ways, this is essentially why I do what I do,” Duval said. “The coloring book is one example of engaging youth and teaching history, touching kids’ hearts to motivate their minds. To show them their own image doing good things. The Crafts’ is the greatest escape ever from slavery, and it’s sad our kids and community as a whole doesn’t know about it … Even a film like Black Panther, great as it is, pales in comparison to the Craft’s real story, which began right here on our streets. And remember, Ellen and William wanted to read. That helped motivate them.”

As for Davis, Williams, and DeCosta, they hope their great-great-grandparents’ story will continue to do good in the world as it becomes better known. Though they haven’t pursued it, they said they wonder if, as history continues to unfold, there are any descendants of the Smiths, Collins, or other connections to learn of and meet with stories to tell.