Black places and spaces: Rebirth of the Roxy and booming baseball legends

By Clarence Thomas Jr.

Photography by Dsto Moore

The first in a series of articles exploring the history of local locations and their storied roles in black culture.

If the walls of two of Macon’s most recognizable landmarks could talk, they’d have a lot to say. What they utter would be invaluable and memorable for current and future generations, and may reverse a significant lack of knowledge about Macon’s Black history. In turn, this knowledge may put the city on an increased path of empowerment and improvement for all residents.

ROXY THEATRE

The Roxy Theatre, near the corner of Hazel Street and Broadway, stands at one of the gateways to South Macon. A literal shell of its former self, the Quonset hut style building conjures up images of “back in the day” military barracks made famous by shows like “Gomer Pyle.” But the style adds to the Roxy’s allure — and its lore.

It was built in 1949 at a cost of $75,000 by Phil Kaplan in Greenwood Bottom, one of several communities of thriving Black residents and businesses. The Roxy was only open nine years, but was a flashpoint of entertainment and economic prosperity for Black Macon at the height of segregation.

During its run, a who’s who of music superstars and entertainers held court there, including Otis Redding, Little Richard and James Brown. When not hosting concerts, the theater doubled as a movie house, complete with refreshments.

Legendary Macon music man Newton Collier remembers the Roxy for the fun it provided him as a youngster coming up in Macon and the gainful employment it afforded him as a young adult.

The 76-year-old was reared in neighboring Tindall Heights and frequented the theater during the 1950s to participate in teen parties and watch movies with friends. Later in life, he graced its stage as a trumpet player for Johnny Jenkins and the Pine Toppers, laying the foundation for his music career with Sam & Dave, Otis Redding and Percy Sledge. The Roxy served as a safe haven and source of community for Collier.

“It was the backbone of the Black theater district. It was surrounded by thriving businesses and served as a gathering place. It needs to be highlighted as a spot that brought Black people together,” he said.

The theater has experienced a resurgence of attention and notoriety the last few years thanks to Macon native Weston Stroud. The Piedmont Construction Group project engineer began his crusade to reopen the Roxy while still employed with Macon Transit Authority.

Following extensive research and guidance provided by members of Turner Tabernacle AME Church, Westside Neighbors United founder and president George Crawley Jr. and remaining residents and business owners of Greenwood Bottom, Stroud found funding through grants and donations and commenced the theater’s comeback.

“The Roxy was the epicenter of Greenwood Bottom. This area was very prolific,” Stroud said. “The Roxy was a place where Black people galvanized their history. It’s a cultural icon that’s not appreciated as much as it should be.”

Appreciation is bound to increase, however, as collective efforts to reopen it continue. Through grants and support from local individuals, groups, the county and others, the Roxy’s reopening is within reach.

Stroud designated the initial use of the theater property as a food truck plaza. The building is privately owned and still in litigation following a tumultuous period, but the back parking lot is owned by Macon-Bibb County. A succession of volunteer cleanups and improvements to the parking area has led to the capacity to now host community events along with family functions.

If all goes well, the Roxy could once again be active. Stroud cites the wildly popular information, art and entertainment chain Busboys & Poets in Washington, D.C., as an example of the possibilities. Its eight locations throughout the city serve as repositories of history through the combination of books, music, art and open mics.

“The Roxy is the last local cultural icon that Black people made relevant. I want it to be a destination for families to come to as a place that provides a historical context of Black people in Macon,” said Stroud.

The Historic Macon Foundation is on board. The nonprofit’s mission is the preservation and restoration of significant sites around the city. Headed up by executive director Ethiel Garlington, it worked with Stroud and added the Roxy to its Fading Five list. That designation put the Roxy in another place as a location of significance and forced Macon to dive deeper into the waters of what’s important, according to Emily Allmond, Historic Macon’s Lanier Education Coordinator. She candidly expressed that Black Macon monuments matter as well.

“It’s super important to talk about, recognize and share all our history. Black people have been victims of systematic oppression for so long,” she said. “We need to acknowledge Black history, celebrate it and lift it up as we do other communities’ history. It’s a way of correcting the wrongs of the past.”

Brandon Harris echoed Allmond’s point. His family has been stakeholders near the Roxy Theatre since his grandfather established Harrell’s Barbershop in Greenwood Bottom in 1965. He and his cousin Daude Harrell continued the Broadway business and are contributing greatly to the comeback of the area as an enclave of Black excellence.

A stone’s throw away from the Roxy, the first-cousins own a boxing gym overseen by Harrell and the recently minted Greenwood Bottom Shopping Plaza, which Harris rolled out in late November. The plaza contains four Black-owned businesses.

A 36-year-old married father of four, Harris supports reopening the Roxy, but wants to ensure that patrons of the theater visit or invest in Greenwood Bottom’s other businesses as well. Harris said this will allow the area to return to its former greatness and ignite a movement of economic empowerment that fueled Greenwood Bottom and its namesake, Greenwood Avenue, the center of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s once booming Black Wall Street.

“It was important for our family to keep our stake in this area. Greenwood Bottom runs deep in our being. We’ve always known the Roxy and this area’s significance,” Harris said.

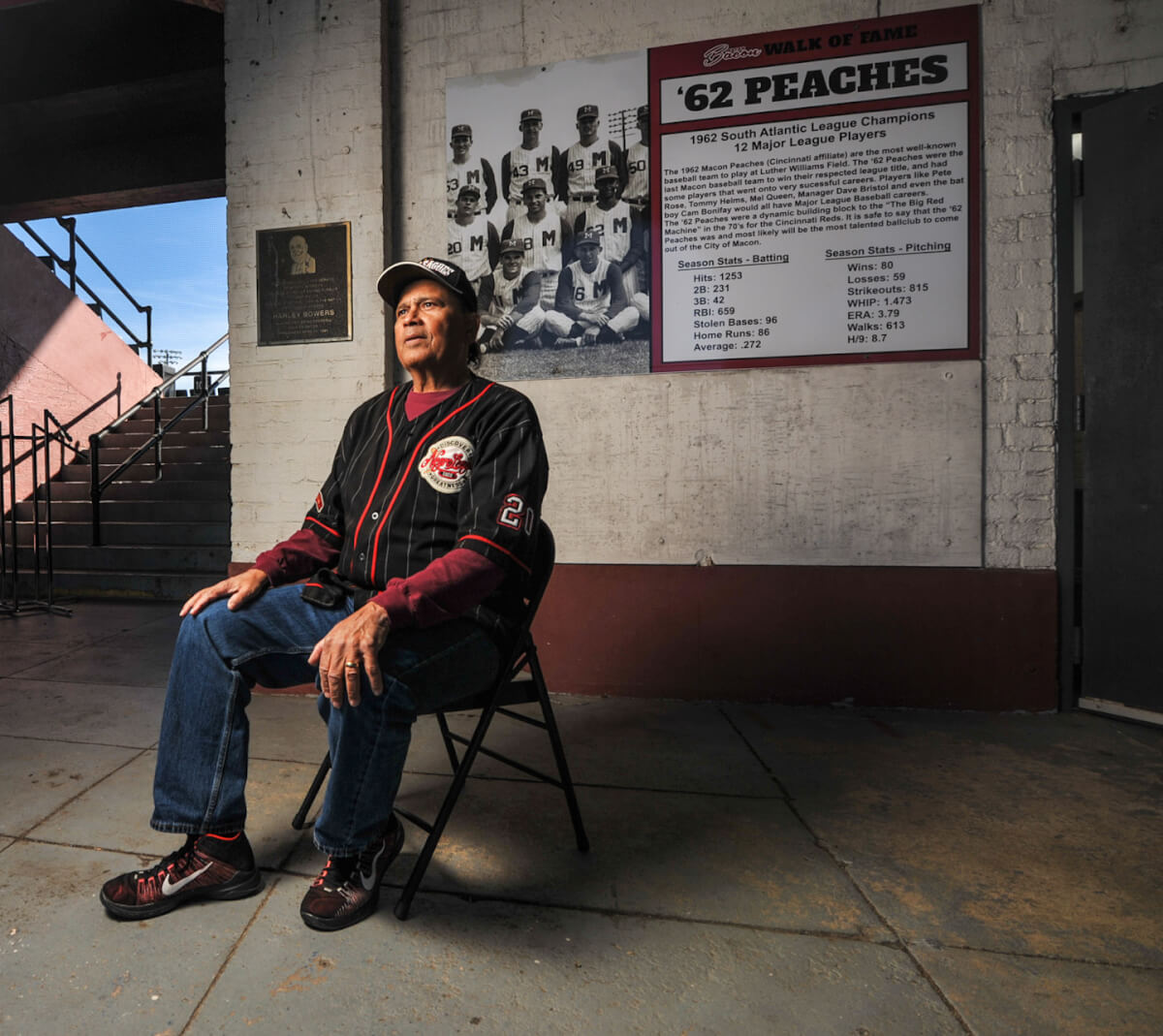

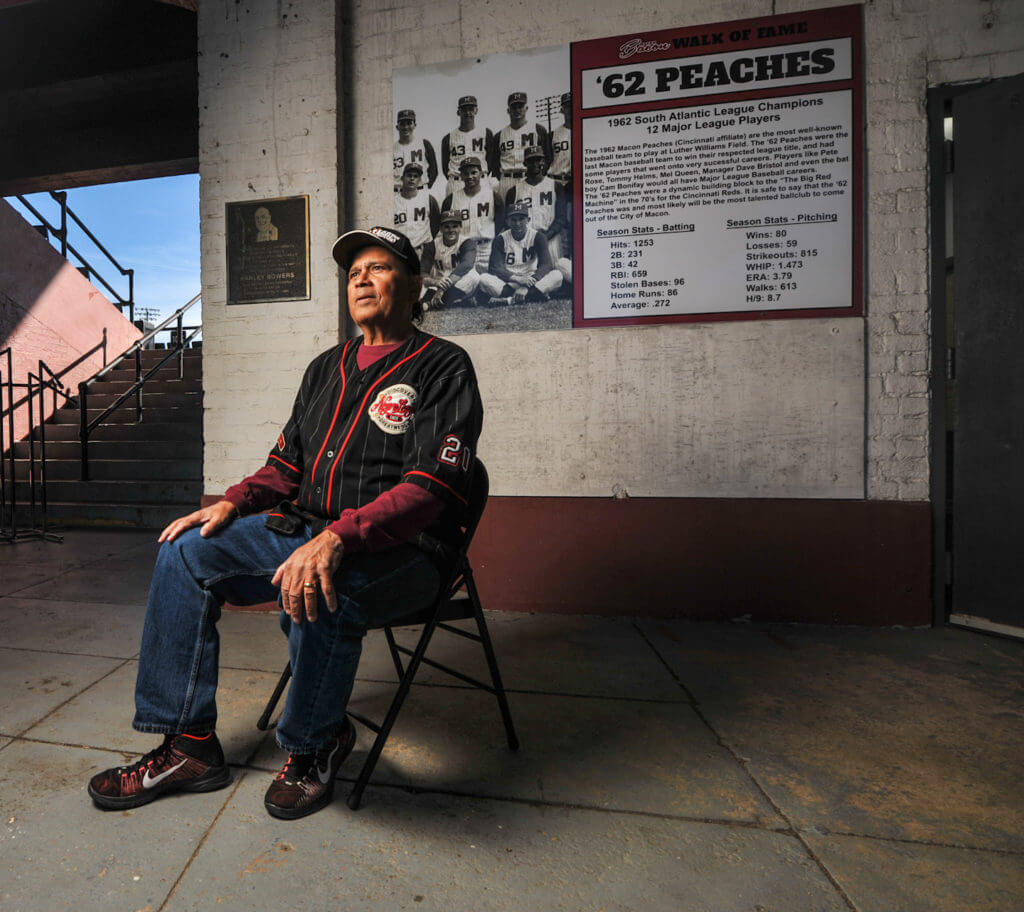

LUTHER WILLIAMS FIELD

Ties that bind Macon’s Black community can also be found in some surprising locations. While youth and young adults may not know it, Macon’s baby boomers and senior citizens are aware of historic Luther Williams Field’s storied past as a place where history and memories were made.

Built in 1929 and on the National Registry of Historic Places, the brick, wood and iron county-owned structure is the second oldest minor league ballpark in the U.S. Named after Luther Williams, who was the mayor of Macon from 1922-1925, the stadium encompasses the eras of baseball that established the sport as America’s national pastime.

Local love of the game transcended the country being separate and unequal at the time, and Luther Williams Field became a launching pad for future baseball superstars and Hall of Famers. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Macon Peaches games played at the park in the 1960s during the hay day of the home team that gave rise to Lee May, Tony Perez, Tommy Helms and most notably Pete Rose.

Evidence of the Negro Baseball League is even at Luther Williams. Four of the league’s most prolific players — Robert Scott, Ernest “Big Dog” Fann, Lemuel Hawkins and Marion Cain — were born in Macon. Bronze plaques that bear their names and brief history as players are on the walls of the park and were dedicated to them in 2016 as a Boy Scouts of America Eagle Scout project.

A Black presence in the form of film is part of the park’s importance as well. Modern audiences have routinely seen Luther Williams Field in movies with baseball backdrops like the Clint Eastwood directed “Trouble with the Curve,” and “42,” starring Harrison Ford and the late Chadwick Boseman as Jackie Robinson. During the 1970s, the park transformed into the primary set for the iconic “Bingo Long Traveling Allstars and Motor Kings.” Set in the 1930s, the film stars Billy Dee Williams, James Earl Jones, Richard Pryor and a host of other ascending Black actors, and focuses on the hilarious, dramatic and tragic ups and downs of a fictious Negro Baseball League team as it navigates the treacherous waters of being a financially challenged, all Black, independent team.

Visit Macon helps keep the park prevalent in the minds of Hollywood as Macon’s main visitor and tourist go-to. Valerie Bradley, Visit Macon’s vice president of marketing and communications, along with Aaron Buzza, vice president of development and chief operations officer, agreed that the park is an asset and deserves to be showcased as a place for all people.

“It’s an important landmark and great attraction that we use as a draw to Macon,” Bradley said. “The park has an iconic look that’s recognizable.”

“Not many parks like Luther Williams Field exist around the country,” added Buzza.

Stephen Duval of Macon recently recalled his role as both an extra and consultant in “Bingo Long.” The 71-year-old is a member of one of Macon’s most renowned Black business families. Duval Upholstery was started in 1883 by his great grandfather, Paul Duval, and lasted until 2003. He and his brothers Paul IV and Thomas assisted in the business coming up, but in between, Stephen Duval managed to squeeze in his love of baseball. He first attended games at Luther Williams courtesy of a kind neighbor in the Pleasant Hill community that treated he and his friends to Macon Peaches games. Duval said the park is part of Black Macon’s history and needs to be promoted as such.

“The stories need to be told. Youth don’t have a big enough connection to history,” Duval said. “If you don’t have a connection to the past, it’s hard to know where you’re headed.”