Conducting Life: A documented beginning

By Michael W. Pannell

Photography by Diane Moore, Dennis Weber, and Susie Knoll

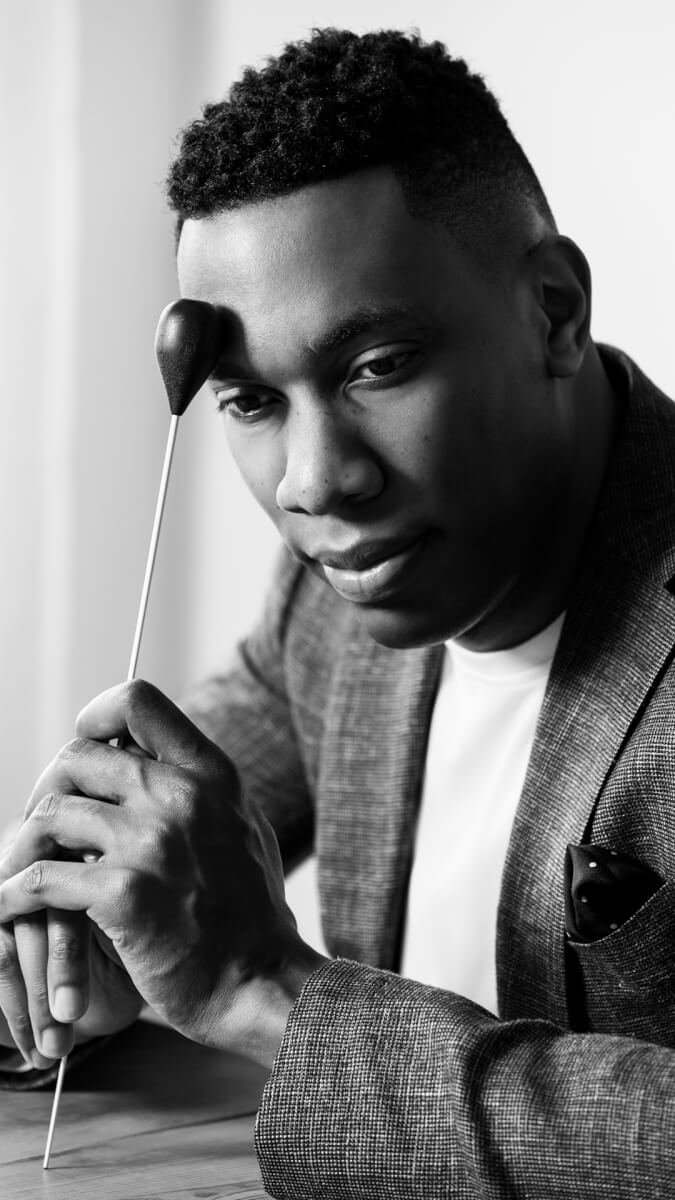

Among Macon’s brightest musical luminaries, Roderick Cox has taken his place on the podium on the world stage.

—

There’s a moment of resounding silence at the start of the symphony, when the conductor steps to the podium – a tangible moment of anticipation when all eyes are on them.

“At that moment, it’s important for me to be firmly and intensely focused on the music and what we’re about to accomplish. It’s a powerful moment – the moment an audience stops clapping and the music is about to be set in motion. Unlike a painting or other art, you’re recreating something that already exists on a page and may have for centuries. You’re involved in an art of interpretation and recreation brought about by hours of painstaking thought and rehearsal.” –Roderick Cox

—

Brenda Cox hasn’t yet seen Conducting Life, the documentary film about her son, and she is more than excited about watching it for the first time during this year’s Macon Film Festival, Aug. 18 – 21.

She’s proud of how she raised him as a hard-working single mom in Macon, along with his brother, Robert, who has also gained notoriety playing high school, college and then professional basketball in Europe.

But Roderick Cox, at 34, is a bona fide star in the classical music world. For a young conductor, he’s won the most prestigious of awards, received sought-after fellowship positions and served in conducting roles, from nearby Georgia and Alabama to his time at the Minnesota Orchestra, first as assistant conductor before quickly becoming associate conductor. Cox was there until 2018, when he moved to Berlin to operate as a featured guest conductor with orchestras worldwide. He’s received high praise with orchestras and groups from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., Seattle to Cincinnati and worldwide in Germany, London and Paris, to name only a few locales.

Though Cox’s mother hasn’t seen the film, she’s had a taste.

“I have seen him conduct in amazing places and seen the movie trailer,” she said. “Seeing him now so good at his music – I can say it fills and thrills my heart. I don’t have the words to describe how I feel. I’m proud of both my boys.”

As portrayed in Conducting Life, Cox’s early life wasn’t an obvious starting point to international symphony stages. He experienced the challenges inherent in a family where the father is absent and the mother takes on added work to make ends meet. He had a loving family and, according to his mother, a supportive church family at Bethany Seventh-day Adventist Church. Gospel music was what filled their home, and his mother was a dedicated choir member. Though she didn’t expect his career choice at the time, she said there were clues.

“He would see the choirs, then come home and set up his action figures and direct them,” she said. “He’d arrange them as sopranos and altos and such as that.”

In public school, Cox was edged toward drums, but taught himself piano at home on a little keyboard his mother bought. At times it was pawned to pay pending bills. Cox said involvement with the Boys & Girls Clubs of Central Georgia was also a factor in his upbringing and led him to the attention of Zelma Redding, widow of the late Otis Redding, and the Otis Redding Foundation. Redding bought him a French horn, paving his way to attend the Schwob School of Music at Columbus State University for true classical training.

“I could see success in Roderick from the start,” Redding said. “He’s proven me right. Providing him with that French horn was a small step. Then all he needed was access to education and opportunity, and the Foundation provided him opportunities by sending him for additional studies abroad. He already had the passion and drive to determine his destiny.”

Finding that his musical vision couldn’t be expressed through a single instrument, Cox gained a master’s degree in conducting at Northwestern University in Illinois and connected with some of the most famous names in the field. He became a favorite at the Aspen Music Festival and studied in Aspen with Robert Spano at the American Academy of Conducting.

This August, before the film’s local debut at the Macon Film Festival, Conducting Life will be shown for the second time in Aspen, this time coinciding with Cox conducting the Aspen Chamber Orchestra during the Aspen Music Festival. Also performing at the festival, and in residence for a portion of it, will be fellow Macon native and violin virtuoso, Robert McDuffie.

McDuffie said he’s been aware of Cox for some time and will bring him home to conduct the Macon-Mercer Symphony Orchestra to open its second season in October.

“Roderick has been on my front burner since the creation of the Macon-Mercer Symphony,” McDuffie said. “He has become not just a conductor but such a significant conductor. It’s insulting to say he’s significant because he’s a conductor of color because he’s simply a good – a very good – conductor. But he’s overcome challenges. I and many others admire him, … and we’re both very proud to be from Macon.”

—

A conductor at his podium reflects years of education and training, plus countless hours in solitude, creating a personal vision for a piece and how to lead through a gesture and baton.

“Take the idea of an actor preparing to portray a character before filming…They would spend a lot of time dissecting and getting to know and understand the character. A conductor spends time getting to know the character of the score, reading it over and over, dissecting and breaking it apart, putting it back together. You let its setting and history speak to you.” – Roderick Cox

—

Cox said a thoughtful conductor will spend months, even years, with a piece of music. Though it may be performed, he believes the process is never complete.

“It’s a huge mistake to think you’re done and that the music has nothing more to say to you or to an audience,” he said. “It always does. You can’t just take a work off the shelf and say, ‘I’ve done that before.’ The more time you spend with a piece, the more it grows and evolves and you bring something different to the audience and orchestra… Because you change and are a different person over time, that informs your view and ability to interpret a piece. It always comes back to the fact making music is a very human thing.”

Cox said despite stereotypes of the temperamental conductor, he’s found the work requires strength and discipline, yes, but also humility and vulnerability.

“You have to know there’s always more to be learned and that learning comes through others and through life’s ordinary experiences,” he said. “We have to experience life if we’re to understand and convey the life, the humanness and emotion of music. And it’s less stressful not having to walk into a rehearsal hall thinking you know everything or be the smartest person in the room. It’s a collaboration.”

Cox said there is a standard vocabulary of gestures to which each conductor applies his own personality. As for batons, in his short career, he has become a collector.

“I guess I’m quite obsessed with finding the baton that fits me perfectly,” he said. “I may find one that feels great and works, but then feel I need a different weight, balance or sense of freedom from it as a flowing part of myself. I guess I have 10 or 12.”

When it comes to his own sentiments about race and his journey as a conductor, it must be acknowledged that, first, becoming a symphonic conductor is a daunting proposition only few have the talent and resolve for. Then, consider less than four percent of US conductors in that rarified group are of color. But Cox is not discouraged.

“Anytime I go to work with an orchestra, I don’t approach it as someone Black looking into white culture,” he said. “I may look at it as an American trying to approach German music to see how I can best conduct and serve the music. It’s not a matter of thinking we need this many Black or white people doing what we do, but the fact we’re all part of a global society intersecting and learning about one another. It’s more of a cultural exchange.”

This worldly attitude is reflected in Cox’s move to Germany, the birthplace of so much classical music. He did it for his art and to help him be the best conductor possible. Berlin has the unusually high number of four orchestras and three opera houses, and Cox said on a recent evening attending a performance, he ran into no less than one well-known conductor and six musicians.

“Seeing and talking with them that way is not likely to happen elsewhere,” he said.

Plus, it’s easier to travel. “Next year I’ll find myself back in London, France, Norway, Spain and other countries. It just works better.”

But still, an NBC News feature called Cox an “African-American conductor making noise in (a) white-dominated field.” Cox said he believes for the sake of all people and classical music itself that the industry must be more diverse. He said the best he can do to promote that is to be his best.

And he is doing more. While in Minnesota, Cox and others began the Roderick Cox Music Initiative, which provides scholarships for young musicians of color from underrepresented communities, allowing them to pay for instruments, music lessons and camps. Not so dissimilar, Cox said, from what he saw and experienced with the Otis Redding Foundation.

The initiative and sentiment behind it were factors in Cox saying yes to the seven-year-long film project resulting in Conducting Life.

—

In Conducting Life, Cox steps up to podiums and to life offering a glimpse of how he got there and what might follow.

“I never wanted this to be a vanity project praising me or making me special as someone who overcame adversity. There are others who face greater adversity to become the special human beings they are. But in light of the Cox Initiative, I believed it could tell the story and inspire others to aspire to an elusive profession. If we’ve done that, we’ve done our work.” – Roderick Cox

—

Filmmaker Diane Moore directed and produced Conducting Life and currently resides in Aspen. Frequently present at Aspen concerts, she said she had long wanted to do a film with a festival student-performer.

“Listening to Roderick’s story in 2013, hearing about his childhood and the struggles his family faced, the absence of his father and the many obstacles he personally met growing up – I knew I had found a story I wanted to tell,” Moore said. “It was a story containing more than what I originally had in mind, and I was captivated by how thoughtful, articulate and passionate Roderick is. He is very confident, can be terribly funny, but he’s also quite humble and shy. I wanted to follow a long-term trajectory of his life and film over a period of at least seven years. He was a perfect partner for the film.”

The work is just over 30 minutes because, as Cox said, “I was only in my twenties when filmed it.”

Conducting Life is an entertaining but useful tool for the Roderick Cox Music Initiative. Moore said as a documentarian, she wants a call to action in her films. Helping open doors for young people of color to the classical world and benefiting the Initiative fit perfectly.

“It wasn’t difficult to get people to talk about Roderick on camera,” she said. “Though his talent and drive alone serve him well, his kindness and talent draw people to want to help. I got a call one day from a woman in Minnesota saying, ‘Hi, I’m a champion of Roderick’s. How can I help?’ She was Yvonne Cheek, a businesswoman who is on the board of the Minnesota Orchestra and helped start the Initiative. She became one of the film’s executive producers and an invaluable ally along with many others. There are a lot of people rooting for Roderick.”

Moore said there are many on board who are appalled at the hundreds of years of racism and long for a day that is more equitable.

“The point isn’t to sweep it under the rug but to put it behind us so skin color or gender isn’t the issue,” she said. “I think Roderick and I are aligned in wanting to look at who people are, what they love, what they’re creating. He’s a conductor pursuing his very best, pushing himself but also wanting to push open doors for others. That message is fairly clear.”

Cox will be in Macon for the film and will participate in a Q&A following the screening.

“I’m very aware of where I came from and its musical traditions,” he said. “Traditions from singing in church to Little Richard to those who followed. Macon is not just a place I’m lucky to be from but a place where great art comes from. I’m proud of that.”