Inching closer to justice for all

By Julia Rubens

Photography by Jessica Whitley and Matt Odom

“One of the things I would like people to know is that the door is open,” Tina Hunt emphasized. In a profession known for charging by the minute and its busy schedules, hearing a lawyer say this is surprising. But as executive director of the Federal Defenders of the Middle District of Georgia Inc., Hunt is willing to take the time to serve.

Far from wondering about billable hours, the legal professionals on her team, who provide criminal defense representation for those charged in federal court, “are all incredibly dedicated to the mission and dedicated to making sure people have a voice – that they are not just a statistic, that they are seen as people.” This enthusiasm is not rare among lawyers who choose service in Macon and Middle Georgia. In fact, there are a number of organizations and individuals with a heart for service here in the heart of Georgia.

MISSION OVER MARGIN

Even in an area where the percentage of persons in poverty is more than double the national average (US Census Bureau, 2020), these professionals working in legal services for the public and nonprofit sector defy the stereotype of beleaguered. They are energized to try to meet the immense need, and the door is eagerly open. “When it comes to federal law, if you have a question, we can probably answer it,” said Hunt, who encourages people to contact the office.

Elizabeth Waller offers the same advice as managing attorney for Macon’s regional office of Georgia Legal Services Program (GLSP). GLSP provides access to justice and opportunities out of poverty through free civil legal services. Though the organization is set up to serve low-income clients generally under 200% of the poverty level, Waller explained that they encourage everyone to call 833-GLSPLAW to see if they qualify. And if they don’t, GLSP still tries to refer them. Trying to make connections for those who have needs, even across a complex web of charitable organizations and government services, is how these leaders practice the law.

When the door opens to District Attorney Anita Reynolds Howard’s office, which serves the Macon Judicial Circuit, she’s often stepping out of it. “If we expect to serve this community from these four walls, we are sadly mistaken. We have got to be intentional about engagement,” Howard said.

In practice, this means some innovative ideas, like bringing along a victim advocate to public events in case citizens have information to share to the office. An emotional support dog, Lamar, sat in Howard’s office during her interview.

Lamar’s role is unorthodox, and not everyone may understand how keeping a pup in the office maintains public safety, but Howard explained that he gets results. For example, a victim of childhood sexual abuse requested Lamar on the day the child was set to testify in their case. Howard won the conviction. “He’s another tool that we use to promote justice,” Howard said about Lamar.

Howard’s community engagement practices extend past prosecution. Keeping up with cases is a time-consuming job, but Howard emphasized that the extra hours spent outside of the court and with people, especially youth, who aren’t involved with the criminal justice system are just as important.

By orienting a number of services towards children before they are in front of the courtroom, Howard is taking a holistic approach to public safety: “I’m a big believer in the science of hope. Believing in yourself, believing in others, believing in your dreams. Allowing kids to believe in others by having that consistency with relationships.” This is particularly important, Howard said, in impoverished communities, where more services can improve outcomes before a criminal offense occurs. “We can’t prosecute our way to safer communities. No prosecutor has ever done that. You’re always going to have more cases than trial weeks,” she explained.

Retired Judge Bill Adams also sees the need in Macon, and, like Howard, is using his extensive experience in the courtroom to transform the world outside of it. After 18 years as Judge of the State Court of Bibb County, he has turned his attention to Middle Georgia Justice (MGJ), serving as president of the board. MGJ is a new organization founded in 2018 to identify the gaps in legal services, then support and supplement existing systems for providing legal assistance to those in need.

To Adams, lessening inequality is at the heart of the work MGJ is trying to achieve. He explained, “We aspire to equal justice under the law in America, but we don’t really have that. For folks who need legal work and can’t afford it, they oftentimes try to handle it themselves. When they get legal assistance, they can overcome obstacles that are keeping them down.”

EVERYBODY HAS A LEGAL NEED

The breadth of services provided out of these Macon offices is as impressive as the depth. Federal Defenders of the Middle District of Georgia Inc. serves a district stretching from the South Carolina border down to Florida state line, then west to the Alabama border. GLSP’s Macon office handles 23 counties in the region. DA Howard oversees cases in not just Bibb County, but nearby Crawford and Peach Counties as well. And MGJ reaches across community partners all around the region from volunteer clinics to universities to conduct their mission.

Legal services can seem opaque as a community need. Complicated documents can change by jurisdiction and require the knowledge of niche specialists. But advocates for justice in Middle Georgia want people to know how essential this work is – and ubiquitous.

“The law should be for every citizen, and the legal system can be right complicated. Almost everybody is going to have a legal need, eventually. When a family member dies, you have a divorce, legitimations for the rights of fathers. Citizens getting legal relief they need is why we need everybody’s support – everyone benefits from the services we’re providing,” Adams noted.

Adams explained that the chain reaction of providing access to justice can transform society. One service MGJ assists citizens with is handling heirs property, an issue in which ownership of a home or other real estate is unclear after an individual’s death. Heirs property contributes to blight and has been called “the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss” by the US Department of Agriculture.

By untangling the legal issues associated with a property, MGJ can assist in getting an heir access to the title, which means a citizen is more likely to stay in the property, pay their taxes and keep up with maintenance. Blight also leads to environmental toxins through illegal dumping and contributes to crime, so clarifying heirs property can be truly transformative.

Access to a lawyer can be key to changing the outcome of someone’s life. “There’s a huge increase in the number of people who can get a protective order when they have a lawyer,” Waller said when explaining GLSP’s work in the area of domestic violence. “Going into court by yourself…is very intimidating for someone without a law degree to advocate for themselves.” Waller explained that an attorney can help a client overcome multiple hurdles. For example, the domestic violence victim may encounter hurdles related to housing stemming from the same instance.

It’s the same in criminal law. “I always say that things don’t happen in a vacuum,” Hunt said about being a federal defender. “It’s very easy for people to look at someone and say, oh, that’s a bank robber. But they don’t know anything about the circumstances that led up to that. It’s important that we tell their stories of how they came to be.” Hunt said she believes that expanded resources to deal with underlying issues like childhood trauma, for example, could be extremely helpful in her work.

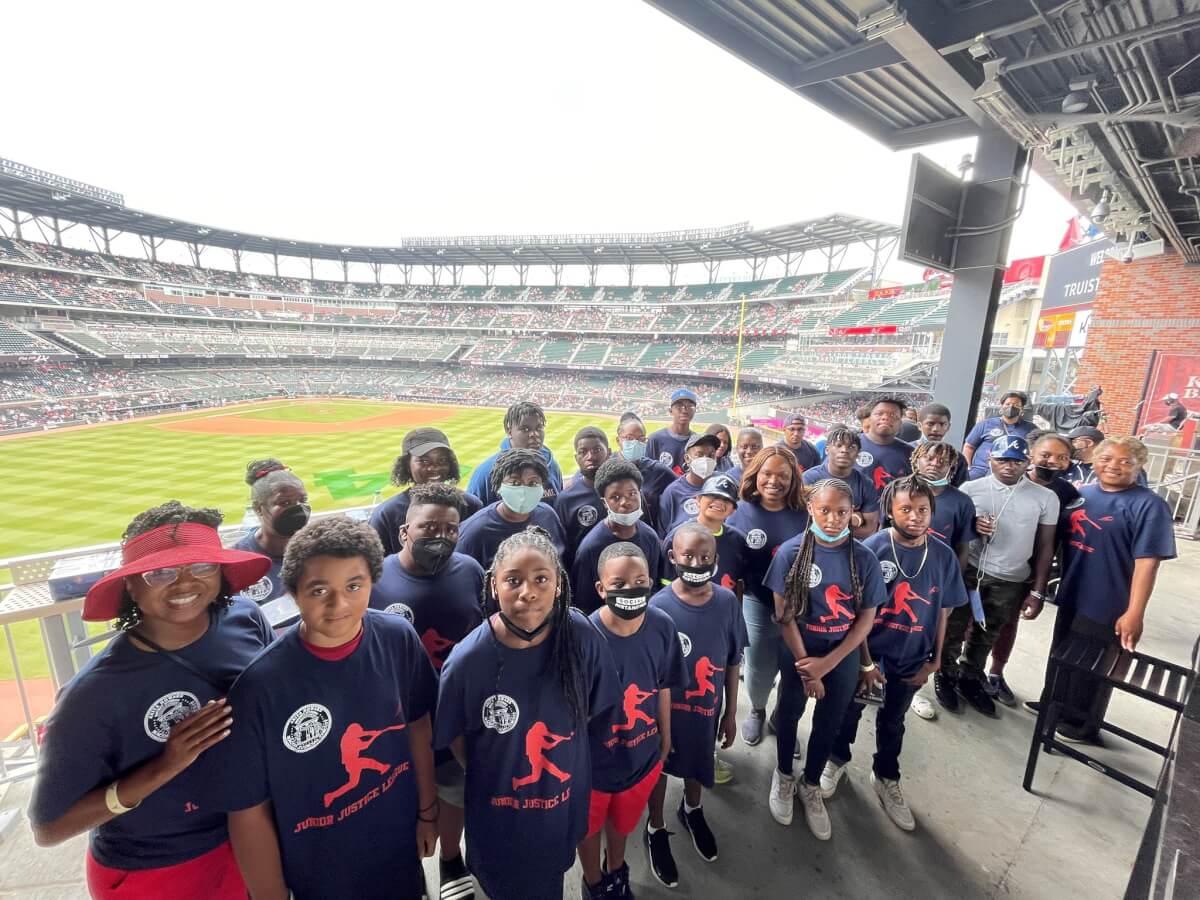

Howard has her eye on trying to mitigate these issues, and she is using an initiative called RISE (Restoring Inspiration by Success in Education) to combat adverse childhood experiences, known as ACEs. “We know that if we can lessen the trauma, or the result of the trauma, then we can increase public safety,” Howard noted. “What you have to realize is that all of this is intertwined.”

MENTAL HEALTH AND RELATIONSHIPS ARE THE KEY

Howard and Hunt, as a prosecutor and federal defender, respectively, would often be seen as being on opposing sides of the courtroom. But both attorneys had a united front when presented by the biggest challenge for lawyers involved in criminal cases: mental health services. Or a lack of mental health services, that is.

“That would be number one to me,” Hunt says. Hunt said she believes that the majority of her clients suffer from mental health issues, and many of these have gone untreated. “The judicial system doesn’t treat those issues, so it’s our job to make change, one person at a time.” Hunt added that she believes that having social workers alongside law enforcement would be beneficial.

Howard agreed: “It’s something that we know that there’s some issue and concern, but trying to figure out what the solution is – it is going to take other officials,” like the state legislature or federal government to expand services.

Another key need is more involvement from attorneys and the greater population. While all of these leaders cited the Macon Bar Association as a great resource for maintaining the legal community, there is still a need for more help in taking on cases. GLSP is always looking for additional lawyers to volunteer.

Beyond just a desire to serve, Waller said that lawyers can get experience in different areas and CLE credits: “Maybe you’re a tax lawyer, but you’re interested in doing a little bit of probate. We can train you. We follow the case through and make sure you have what you need. It’s a great way to get your feet wet,” by taking on pro bono cases through GLSP.

Since so many attorneys identified the complex web of services involved with the law, collaboration and relationships are key. With MGJ, “We just try to complement and fill the gap – the justice gap. We find an approach of collaboration with existing resources in town to identify the gaps and who can fill them. In Macon we have a number of great nonprofits and ministries that really work well together,” Adams explained.

And one doesn’t have to be a lawyer to help fill the justice gap. Adams said donations to MGJ are especially helpful, and the organization hosts an open fundraising event called “A Taste for Justice” at Luther Williams Field each year to further their work.

There’s another way that any citizen can support the need for justice. Hunt is emphatic that everyone has a part to play: “I wish more people realized it’s a privilege to be a juror. Most people get that piece of paper and say, ‘Oh my gosh, how can I get out of this?’ But that’s how our system works. There’s grey areas in the law. It’s never black and white. And jurors are truly essential to filling that need.”

The needs can feel overwhelming when the gap towards justice is persistent, but it only makes Howard more determined: “I’m not closed off to the fact that there are concerns, especially in impoverished communities, communities of color, when it comes to law enforcement. There’s a mistrust there, but that’s why I’m out in the community. How do you build trust with someone? By being present.”

The passion that unites the legal community involved in public service work is admirable. Keeping the door open for the community can’t be easy, especially in Middle Georgia’s wide service region and poverty levels. But the work is gratifying, too: “It’s not just a job. It’s not just a career. It’s my whole belief system that people’s stories should be told,” Hunt said. “I feel very privileged to tell those stories.”